Lumbering in Hancock County

…when timber was king

Russell B. Guerin – originally prepared in part for inclusion in joint project with Marco Giardino, Early History, Hancock County, MS, unpublished manuscript

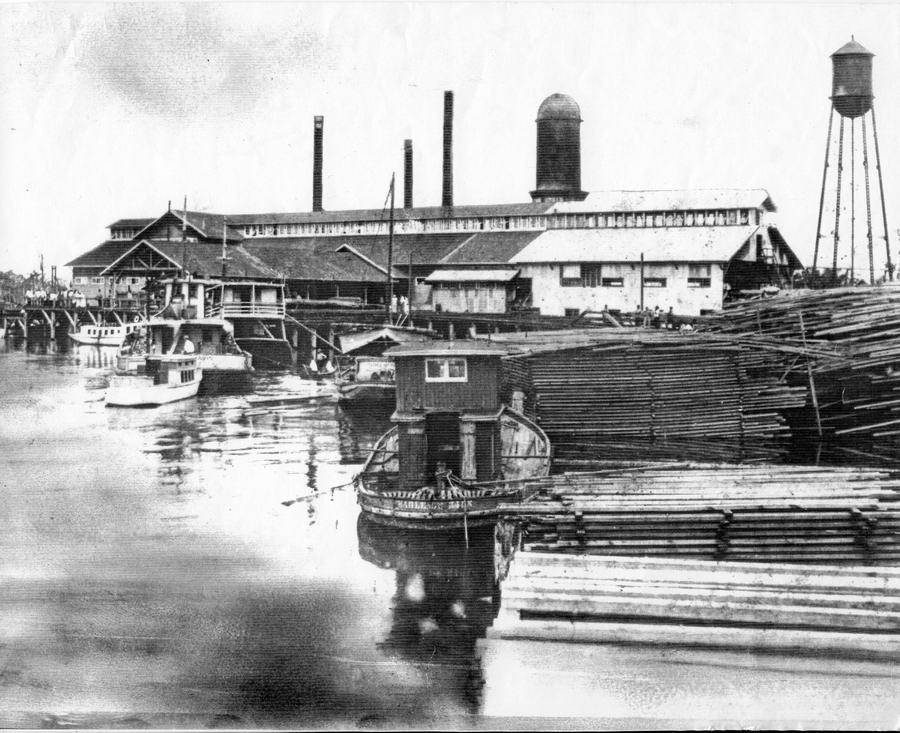

Edward Hines Lumber Company, Kiln

Edward Hines Lumber Company, Kiln

Though lumbering became Hancock County’s primary industry in the 19th century, it may not have been the primary reason the early settlers came to the area. As Peter Chester, provisional British governor in 1773, pointed out, “Those tracts which have been applied for since my arrival in the province, have only been Granted to such persons as gave me the strongest assurances, in Council, of their intentions to Cultivate and Improve the [land], excepting such as have been granted in consequence of His Majesty’s Orders inn <sic> Council, and in consequence of his proclamation in 1763, to reduced Officers who had served during the late War in North America.”

But Chester also wrote, in telling of the land where Favre settled, “The Land here is not extraordinarily high but seemingly fertile upon the Banks and back it is Pine Barren, the Trees of which are large and fit for Turpentine.”

W.C.C. Claiborne sang the praises of the area as early as 1811. In a letter to Secretary of the Navy Hamilton, he wrote on July 2nd from Pascagoula, “The lands bordering on the lakes Maurepas, Pontchartrain and Borgne abound in Live Oak of the best quality, and near the Florida Shore, and on several islands in this vicinity, it also grows Luxuriantly. On the Pearl and Pascagoula Rivers, & the Waters of the Tombigbee, I learn there is an abundance of Cedar, Mulberry and Locust, the Cypres <sic> of the Mississippi is enexhaustible <sic>….” 1

In May, 1846, the word “inexhaustible” was also used by the Gainesville Gazette to describe the quantity of the timber available. The word was echoed by DeBow’s Review in 1852.2

The latter stated, writing about the area around the Bay of St. Louis, “The timber of this region, as well as along the entire sound, is inexhaustible, and the facilities for getting it to market very great…. No section of our coast presents greater advantages for trade in lumber than Mississippi Sound. The lumber is inexhaustible.” 3

Some of our early history includes information that timbers of the Logtown area were utilized to construct Fort Pike after the War of 1812. The census of 1820 records 153 people engaged in agriculture, another 312 in commerce, and 130 in “manufacturing”; the latter may be guessed to have been, in fact, the lumber industry. Still, lumbering on the Pearl did not become the primary enterprise until the 1840’s.

Pearl River – an artery

Pearl River was at the heart of the success of the lumber industry. In the days of the early settlers, the water was clear, and possibly drinkable. It was navigable but relatively slow, making it possible to “raft” cut trees to the mills. The finished product could easily be shipped downstream to ports like New Orleans and Mobile. Even the fact that the river was tidal must have been occasionally an advantage to vessels going upstream. Several issues of DeBow’s Review commented on the Pearl’s value; one article considered the need to make the Pearl more navigable in connection with the possible building of a railroad from Jackson to Ship Island.4

When W.R. Wingate secured 1600 arpents from Joseph Chalon is not known, but it is said that there was already a mill at the site. Wingate built a larger one, probably in 1845-1846. This was later to become known as Logtown, the locus of the Weston mill. It was reported that the Wingate mill was capitalized at $20,000 in 1850 and had a capacity of 5,000 board feet per day. In that year, there were 14 workers and the monthly payroll was $210.

The Mills, a Comparison

For comparisons, Louisiana’s Loss, Mississippi’s Gain, by Scharff, quotes from the U.S. Census of 1850 and lists the following sawmills located at on the lower Pearl:

William Poitevent’s mill at Gainesville was capitalized at $7,000. Its capacity was 5,000 feet per day, using 12 laborers with a monthly payroll of $300. It cut 1,760,000 feet in 1850, valued at $223,000.

J.B. Toulme and D.R. Walker had a mill capitalized at $9,000. It had a crew of ten workers with a payroll of $150. Annual production was estimated at 1,200,000 feet, with a vaue of $96,000.

W.M. Brown of Shieldsboro grossed $11,200 at a mill employing eleven men and two women.

Asa H. Hursey and a Mr. Henderson owned a mill at Pearlington with a capacity of 3,000 feet per day. It was capitalized at $4,000. Nine men were employed, cutting 700,000 feet per year, valued at $84,000.

In addition, a search of the Hancock County deed books reveals that a number of other, perhaps less prominent, settlers were involved in logging, if only peripherally. In 1853, Asa Hursey sold to Thomas Brown a 535-acre tract and “also our schooner boat lying at the Wharf at Pearlington which is not yet named but intended to be called the Isabella with all her rigging and appointments, also 200 logs partly pine and partly cypress lying at the river at Pearlington.”

Also, in 1853, there was recorded an agreement between G. W. Peoples and Robert Montgomery, (a resident of Napoleon) having to do with a mill with a circular saw on Pearl River. It was stated that Peoples was familiar with the operation and therefore given the “right to operate and the right to profit until September and possibly later.”

De Bow editorialized in 1854 that “the sawing of lumber, farming and distilling turpentine, are now the most profitable kinds of business near the seaboard and out of the city.” A year later, DeBow commented on a proposed railroad that was to run along the Gulf Coast and to Ship Island at the cost of $ 3,000,000. In that article, the New Orleans

Bulletin was quoted: “If the Mississippians would spend $100,000 judiciously, in rendering Pearl River navigable, they would do more for that section of the State than they can by embarking in the proposed railroad experience.” 5

Production along the Pearl seems to have changed quickly in the next few years. Weston and the Carre’ brothers bought the Wingate mill in 1856. DeBow reported in 1859 that exports in lumber, wood, and charcoal from Bay St. Louis amounted to $100,000. Seven mills were producing one million feet of lumber annually. Thirty to forty vessels were operating, and it was said that the facilities for getting goods to market were great. DeBow also reported contracts with France to ship thousands of spars of all dimensions for navy ships. It was indicated that lumber was shipped via Mobile.

J.F.H. Claiborne in a letter to the editor of The Mississippian in 1857 stated that the mills located on the margins of the small streams which emptied into the Gulf annually supplied forest products to fifty cargo vessels from all parts of the world. During the latter half of April 1857, lumber, sawed timber, and deals to the value of $28,000 were shipped to England and Australia. “In addition,” wrote Claiborne “our trade in lumber coastwise, that is to say with Texas, Mexico, and the West Indies is enormous,” and “Mississippi pine is now sent on almost every steamer that leaves New Orleans for St. Louis.” 6

Civil War Effects

The mills continued to grow until New Orleans capitulated to Union forces in 1862, which resulted in a blockading of the market. It can be seen from the Koch family papers that some few struggled with intermittent logging operations through the war, but the Pearl essentially was stripped of its commerce except for an occasional permit.

After the war, lumbering again prospered. In Baxter’s history of his family – A Baxter Family from South Carolina – he tells of the great success of the Logtown [Weston] mill: “At its zenith the company’s holdings were almost 2 million acres in Mississippi, Louisiana, Mexico, Oregon, and British Colombia. Its markets had expanded from domestic to international with much of its lumber going to South America and Europe. It became the largest lumber mill in the world. At its zenith it had a capacity of producing 30,000,0000 board feet per year.” It had its own railroad, commissary, and a power station, ice house, livery stable and telephone company.7

H. Weston Lumber Company and Poitevent and Favre Lumber

Of all the mills, it appears that the Weston mill and the Poitevent and Favre Lumber Company were the most significant over a long period. To adequately consider their history, a chronology is in order.

Weston

In 1849, Wingate 8 hired Henry Weston, a young man from Skowhegan, Maine who was working at the Poitevant mill in Gainesville. In 1852, De Bow’s reported that contracts had been made to provide thousands of spars of different sizes to the French navy.9

In 1854, Wingate transferred the mill and the Challon land claim, known at this time as the “Logtown Tract,” to his cousins the Carre brothers and John Russ. The latter sold one-third back to Wingate, who later conveyed it to Henry Weston.

The mill burned in 1856, and was rebuilt in 1870 a short distance from the old one. It was located alongside Bogue Homa. It may be guessed that the Civil War delayed the rebuilding, but it is noteworthy that Weston mined salt on “the Lakeshore” during the war.[10]

Weston married Lois Angela Mead in 1858.

In 1861, records of the mill show that $20,000 was paid for slaves. Salary for each partner at the time was $5,000.

In 1874, the Carre ownership was dissolved, leaving Wingate the sole owner.

Two new partners, Otis and Beach, were taken into the firm in 1888. About this time, it was said that this was the largest mill in the world, owning 150,000 acres, a railroad and a company store.

Besides the land in Hancock County, there were additional holdings in Louisiana, Mexico, Oregon and British Colombia, amounting to two million acres. At peak capacity, the company produced 30,000,000 board feet per year.

Henry Weston died in 1912. It was about this point in time that the fact was recognized that timber was indeed exhaustible. By 1913, the Weston mill was the only one near the mouth of the Pearl.

In 1923, a report was made by a New York firm of forest engineers regarding “the present condition and future possibilities” of the company. The engineers attempted to pass through every section at least once, making a thorough study of the holdings. Their report was in five sections, only one of which described “reproducing areas.”

The mill ceased sawing new lumber in 1925, and closed in 1930.

Poitevent and Favre

Officially, this partnership of John Poitevent and his brother-in-law Joseph Favre was not begun until after the Civil War, but it had a predecessor. The Father of John, William Poitevent, had been a partner in a saw mill at Gainesville in the 1840’s. It is recorded that “he made a fortune in shipping lumber around the coastal United States” using his own fleet of schooners. Married to Mary Amelia Russ, they had eight children, the second of whom was the partner of Favre, mentioned above.

Joseph Favre was a grandson of Simon Favre, and son of “Gus” Favre.

Poitevent and Favre started their business at Pearlington in 1866. Poitevent married Emily Toomer, whose sister Rebecca Toomer married Favre. (The Toomers were also in the lumber business, apparently on the West Pearl, in Louisiana.)

One group of documents, called the Eads Poitevent Collection, is housed in the special collection section of the University of New Orleans library. It mentions that by 1870 the Poitevent and Favre lumber company “was the largest mill in Mississippi, employing over 150 workers. The company supplied lumber, ties and pilings for the building of bridges to the Mobile and New Orleans Railroad Company and provided materials for the jetties constructed at the mouth of the Mississippi River for James B. Eads in about 1874. The brothers-in-law also owned three mills and a shipyard at Pearlington and operated a line of steamers and schooners which transported lumber …to foreign ports.”

Another source, Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Mississippi, claims that the company had become the largest plant of the South, producing annually forty million feet of lumber, owning many large schooners, a stern-wheeler, and four tug boats. In addition, the company created the East Louisiana Railroad, which could haul 1,000 logs per day to the river. The company owned three retail stores at Pearlington. Holdings include 95,000 acres in Hancock County and in St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana.

In 1884, lumber was furnished for the construction of the New Orleans Cotton Exposition in New Orleans.

Poitevent and Favre had a new mill built in 1890 by Asa Hursey, said to be the finest mill builder in the country. Called “Big Jim,” it could cut 200,000 board feet per day for loading on the company schooners for delivery to other ports. At the time of construction, it was said to be the largest, but in twelve years became one of only medium size, as compared to others that had come along.

In 1899 John Poitevent died and was succeeded by Joseph Favre as president. After a short time, the latter sold to Frank B. Hayne, who became majority stockholder. By 1904, Hayne had cornered the market in cotton and was reputed to be worth 100 million dollars.

Eventually, timber became too scarce for the Pearlington mill to continue. In 1904, it was closed, leaving Pearlington a dead city. Hundreds were laid off, many moving to Slidell, Louisiana and other logging locations. Sam Russ, who had been clerk at the 200-foot long commissary when its warehouses were full, said, “The mill was built to last 100 years, but …[they] overestimated the supply of timber upriver.”

A move of the company to Mandeville, Louisiana was necessary in 1913, leaving the Weston mill the only one remaining near the mouth of the Pearl.

Aftermath

Today, many of the acres which once boasted huge stands of virgin cypress and pine are barren; others are cultivated for the purpose of growing and harvesting pulp wood. Life as it was known in the communities along the Pearl does not exist anymore. People had begun moving away even before the Stennis Space Center required several of the towns to be razed and reduced to ground level.

But the passing of an industry is not to be mourned. For many years, men were employed, and their families were fed. They did honest, hard work, sometimes back-breaking, like sawing huge trees, rafting the logs in the river, loading the boats and sailing them to far-off ports. Some men indeed became rich.

Memories remain, and cannot be erased by clear-cutting, burning, construction or hurricanes. History rightfully records that a great industry contributed to the building of the Hancock County we know today.

1 Claiborne, Letter Books, p. 286.

2 The Gainesville Advocate, May 9, 1846.

3J. G. Harris, “Climates and Fevers of the Southwest,” DeBow’s Review, vol. 27, p. 596

4 “Railroad Progress in Mississippi, Florida…,” DeBow’s Review, vol. 18, p. 260.

5 “Railroad Progress…,” DeBow’s, p. 260.

6 Nollie Hickman, Mississippi Harvest: Lumbering in the Long Leaf Pine Belt, 1840-1915, p. 33

7 Roy Baxter, unpublished manuscript, Hancock County Historical Society.

8 Listed in the 1850 census is David R. Wingate, a 30-year old lumberman with a real estate value of $3,000. He was born in South Carolina. One of his sons is named as Robert P., probably after his grandfather, found in the census as a 60-year old farmer from North Carolina.

9 “The Harbors, Bays, Islands, and Retreats, of the Gulf of Mexico,” De Bow’s Review, November 1859, vol. 27, p. 596.

10 Roy Baxter, Sea Coast Echo, Jubilee edition, May 28, 1978