The Pirate House and Jean Lafitte

Russell B. Guerin for the Hancock County Historical Society

The Pirate House, 649 North Beach Boulevard, Waveland, before Camille.

The Pirate House, 649 North Beach Boulevard, Waveland, before Camille.

Judging by the photos in our Lobrano House collection, the Pirate House had to be one of the most imposing - as well as one of the most beautiful - structures on the Hancock County coast. It must have been designed and built by craftsmen of more than ordinary talents, for it was at once large, strong, and handsome.

Regrettably, Hurricane Camille demolished the Pirate House in 1969, even though it had survived many storms over the years. If it had not been destroyed, perhaps even now there might be a clue to be discovered that would alleviate some of the mystery that lingers in the legends.

And mystery there is. When was it built and by whom? Was it a transfer point of contraband slaves? Did the noted pirate, Jean Lafitte, have some connection to the house, perhaps even by way of ownership? Was it really possible to have a tunnel from the house to a sandbar, allowing for the discreet disembarking of “black ivory,” as the legend forcefully tells?

The WPA report of 1938 states that the “Pirate’s House [was] built in 1802 by a New Orleans business man who is alleged to have been the overlord of the Gulf Coast pirates. At one time, the legend says, a secret tunnel led from the house to the waterfront….The house is a perfect example of the Louisiana planter type, with a brick ground story and an outside stairway leading to the first floor. The outer walls are covered with white stucco; square, white frame columns support the gallery, which runs the length of the house. The three dormer windows on the front are beautifully proportioned, and the iron grillwork forming the banisters is reminiscent of that in the French Quarter in New Orleans.”

Other than the above, not a great deal is recorded in our library to authenticate the stories of the Pirate House. The file in the Lobrano House is indeed a very thin file. While much of what is said has been passed down orally through generations, it should be recognized that legends - even those that may seem far-fetched - usually have some basis in fact.

Consider for example the story of the tunnel. Even with modern technology and equipment, the construction of a tunnel out to open water would be a challenging endeavor. But the legend is strong, and there have been eyewitnesses to attest to its existence. One story still told is that workers constructing the beach road in 1928 uncovered part of the tunnel.

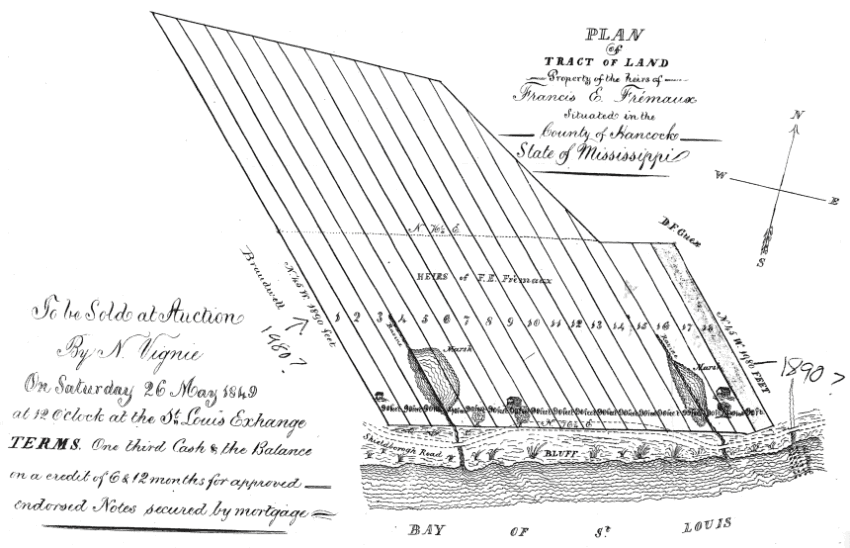

The Pirate House stood next to a small bayou and pond. These natural formations, still in existence, are shown in several of the earliest maps of the area. They are contained in Deed Book A in the Courthouse, and called the Francis E. Fremaux tract. (See below)

Francis E. Fremaux tract

Francis E. Fremaux tract

This is possibly significant because it is probable that the little bayou and the pond would have been shrouded by trees and brush in the early 1800’s, adding cover to the activities of any illegal endeavors. Certainly, the site would have been very secluded in those days, and small boats could well have gone into that pond to secretly unload contraband cargo.

Much ballast stone - even now - has been found in the immediate area. It seems right to postulate that the house was built next to the pond and bayou for a reason.

Concerning other parts of the legend, it should be noted that our Lobrano House collection does indeed record stories about pirates. And these deal not only with legends of those that plied the local bayous and Honey Island swamps, but also authentic historical recordings. Consider, for example, a letter from Joseph Collins, then the administrator of Pascagoula and the Bay of St. Louis, written on October 17, 1806, regarding travel to New Orleans and mentioning “…frequent invasions of Boats and Launches of the enemy corsairs that sail for these passages.” Another letter of December 4 of the same year, from an official of Spanish West Florida, states: “As per the part of Benito Garcia of a small Ship of traffic and commerce on these coasts, as formally denounced to me, that in the post of Pascagoula, will be disembarked twenty-one blacks of contraband.”

In the early 1800’s, trading in and importation of slaves was legal in the fledgling United States, thus prompting the question as to why would pirates, Jean Lafitte or others, have to be secretive in their operations. The answer is found partly in the Constitution of the United States and partly in the charter given to Louisiana after the purchase in 1803. Although the Constitution, in Article I, Section 9, paragraph 1, allows for continued importation of “such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit” until the year 1808, Congress outlawed such importation in Louisiana. This was at the suggestion of President Thomas Jefferson, who had attempted to do the same for the thirteen states in his initial wording of the Declaration of Independence, but was thwarted by the Continental Congress in the final draft.

By way of background, Jefferson’s position on slavery was an anomaly. While he owned slaves and, it is believed, had children by Sally Hemmings, his writings were decidedly anti-slavery. At his suggestion, Congress established the government of Louisiana on the basis of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which outlawed slavery. Moreover, he appointed as governor of Louisiana W.C.C. Claiborne, whose writings show clearly that he hated the institution of slavery. In a letter to Jefferson dated November 25, 1804, he stated, “The Searcher of all hearts knows how little I desire to see another of that wretched race set foot on the shores of America.”

But Louisiana and its plantation economy craved more slaves. In the same letter as above, Claiborne wrote, “But, on this point, the people here are united as one man. There seemed to be but one sentiment throughout the province. They must import more slaves, or the country was ruined forever.”

Regarding Claiborne’s problem, Charles Gayarre, in his History of Louisiana, was later to write, “Negroes were daily smuggled into the territory through the Spanish possessions by way of the lakes Borgne, Pontchartrain, and Marepaus.”

It is reasonable to assume that Jean Lafitte knew of the circumstances and their resulting opportunity for profit. Certainly, the Waveland and Bay St. Louis coasts and Pearl River, because of their proximity to the back door of New Orleans through lakes Borgne and Pontchartrain, must have been ideal locations for the transport of contraband slaves in that period.

It is probably not coincidental that another house shared the same legend with the Pirate House. This was known as Laurel Wood Plantation, located on Mulatto Bayou, a tributary of Pearl River. It was also believed to have been a transfer point of slaves. (This was built about 1800 by one of the Sauciers, and eventually became the home of another Claiborne, being Colonel JFH Claiborne.) Before the house was torn down in the development of Port Bienville in the early 1960’s, eyewitness accounts had recorded that there were “cages” under the house.

This sketch reputedly shows Louisiana pirate leaders drinking in a cafe in New Orleans in 1812. From left to right, the men are traditionally identified as Renato Beluche, Jean Lafitte, Pierre Lafitte, and Dominique You. (Courtesy, Louisiana State Museum)

This sketch reputedly shows Louisiana pirate leaders drinking in a cafe in New Orleans in 1812. From left to right, the men are traditionally identified as Renato Beluche, Jean Lafitte, Pierre Lafitte, and Dominique You. (Courtesy, Louisiana State Museum)All of the above notwithstanding, one must now inquire into that part of the legend involving the persona of Jean Lafitte the Pirate. The name Lafitte appears a number of times in the written records of Hancock County. Various spellings are evident: Laffite, Lafito, Laffiteaux, and Lafitto. These include official documents such as deeds, probate records, and census reports. The most curious records are dated substantially later than the 1803-09 period, noted above as important years in the study of the slave trade. Beginning in 1825 and going to 1850, there are no less than five deeds showing the real estate activity of Jean and Clarisse Lafitte. Even more interesting is the fact that the 1850 deed recites a sale of forty acres by Clarisse to Jean Defour. That document traces a chain of title to one Mary Parish, who in 1833 had been awarded 639 acres by the United States government. (An earlier document indicates a claim by Mary Parish and the Widow Moran. The latter was possibly a parent of Parish, who identified land in another deed as having been property sold “by my mother and father.” It must be stated, however, that genealogical tables do not confirm this.) The acreage so described in several of these deeds was the land, or very near to the land, which included the Pirate House.

It would be easy to jump to a conclusion at this point, but a couple of unwelcome facts raise their heads. One is that Clarisse’s forty acres appears to have been located east of the Pirate House site, perhaps as distant as the shore of the bay. Another involves the date of death of Lafitte the pirate as probably 1825 or 1826, depending on which historian is selected. Believed to have been born about 1780, the pirate would have been about 45 years old at the time of the 1825 purchase.

This does not square with the first mention of John la Fito, found in the 1820 census. At that time, he was between the ages of 16 and 26. The 1850 census is consistent with this, showing an age of John Lafiteaux as being between 40 and 50. Something very intriguing, however, is to be found in the 1830 census, that being the inclusion of another male in that household, whose age was between 40 and 50. This would have been the right age bracket for Lafitte the Pirate. This fact, coupled with the deed of 1825, invites speculation.

The 1825 deed is very curious. It has been preserved in the county deed book even though it long preceded the fire that destroyed the Hancock County courthouse. It is written in French, and a translation seems to evidence that this Jean Lafito was held in high esteem. Whereas two important personages, Noel Jourdan and Charles Nicaise are referred to as simply “misters,” Lafito’s appellation is translated as “sir” or “lord.” It is unlikely that such honor would have been paid to a very young local resident, but to a noted pirate, a hero in some respect at the battle of New Orleans only ten years before? Not proof, of course, of anything, but it can hardly be argued that the difference in referring to these people was accidental.

There is reason also to speculate about the time of Lafitte’s death. Most historians seem to agree that he died about 1825. Alcee Fortier wrote that he died at Cilan in the Yucatan in 1826 and “was buried in consecrated ground.” The “Handbook of Texas Online” states that Lafitte “abandoned Galveston early in May 1820 and sailed to Mugeres Island, off the coast of Yucatan….In 1825, mortally ill, he went to the mainland to die.” Lyle Saxon wrote in Lafitte the Pirate that he died of fever and is buried at Silan, Yucatan, in 1826. He cites several letters as evidence, dated 1838 and 1843, written by people who made no claim to firsthand knowledge of the matter.

At first blush, the most convincing argument is to found in a book published in 1843, Incidents of Travel in the Yucatan, written by an American explorer. This was John L. Stephens, who had hacked through Mayan jungles in the Yucatan for some time before the publication date. The objective of his travel had nothing to do with pirates in general and certainly not Lafitte particularly, and it is for this reason that evidence that Stephens gave might be considered trustworthy. In short, he had no axe to grind.

Stephens reported that the Isle of Mugeres had been the home of the pirate Lafitte, known locally as Monsieur Lafitta, where he was well respected by the townspeople. In the area, he met a local patron who had been a “prisoner” of Lafitte for two years. It was suspected that he actually had served with him in his piracies, as he was certainly fond of his memory. He told Stephens that Lafitte had died “in his arms, and that the widow, a senora del Norte from Mobile, was then living in great distress in Silan.”

After journeying to Silan, Stephens sought out the local padre, who did not know whether Lafitte “was buried in the campo santo or the church, but supposed that, as Lafitte was a distinguished man, it was the latter.” But the grave was not found in the church, and so the padre inquired of some of the locals who had been there at the time of Lafitte’s burial. It is here that Stephens’ testimony, while believable, curiously lends to the possibility that Lafitte may have mysteriously vanished. It is therefore in order to quote directly the passage: “The sexton who officiated at the burial was dead; the padre sent for several of the inhabitants, but a cloud hung over the memory of the pirate: all knew of his death and burial, but none knew or cared to tell [italics by this author] where he was laid.”

And so a new question arises out to Stephens, and causes one to ponder whether Lafitte’s death and burial may have been faked, thus allowing him to continue his life elsewhere without notoriety.

Why must a reader allow for the possibility of such a death being feigned? Lafitte had returned to piracy after New Orleans, thus voiding his pardon. He organized a large band at what is now Galveston in 1817, but two years later, Congress enacted laws making a capital offense of piracy. Called the “beginning of a crackdown,” fourteen men were sentenced accordingly under the terms of the act of Congress (Louisiana, Yesterday and Today, Walter J. Cowan). Lafitte left Galveston as a consequence of attacks made by some of his pirates against U.S. ships. As he was no longer welcome there, he burned his village and went to Yucatan. He was then hunted by both American and Spanish officials.

It is not out of the realm of possibility that a man growing older and less adventurous might have returned to close ties made many years before in a little populated area like Shieldsborough and environs. It is not out of the realm of possibility that John La Fito, who may have been as young as 16 when listed in the 1820 census, might have been the pirate’s son.

While it may be that the Lafitte who made the real estate purchases in Hancock County was not the pirate, one cannot help but wonder whether there was a family connection. Besides Jean and Clarisse, Shieldsborough had Auguste and Marie Laffitte, also property owners. They had at least three children born in the mid-1800’s, all baptized in the local Catholic church. There was also a slave of Auguste named Polomie, whose son was baptized in the same church and was christened Victor Laffitte. Mrs. Lafiteau (whether she was Marie or Clarisse is not known) had a slave named S. Rosine, who fathered a child also christened in the church; she named him Jean Wilfrane Lafiteau.

Relatives of the pirate? At best, we can only say perhaps. The disparity of ages does militate against any stronger assumption, but it is still instructive to follow Clarisse to her death, just in case she might have been the right Mrs. Lafitte. Her will, signed with an “X” on October 31, 1857 and probated on February 22, 1858, describes her property as being “300 feet deep and the same width as that of John Fayard.” This land, which included her house, was sold by the estate for $650. After the giving of three slaves to her friends, her personal estate was auctioned for $29.65. Debts of $388.50, including legal fees of $300 (“an act of R. Seal for professional services rendered in said estate”) were satisfied by the sale of the land.

If Clarisse somehow was the widow of the pirate, she had little to show for all the fabled wealth he derived from his adventures on the high seas.

In summation, mysteries abound about the Pirate House. It is perhaps significant that any attempt to disprove the legends results only in the recognition of possibilities.

Article by Russell B. Guerin, Hancock County Historical Society

Update

In light of new evidence obtained by Mr. Guerin in 2011, a second article on the presence of pirates in Hancock County has been published by him. Please continue reading The Pirate House Revisited.