This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

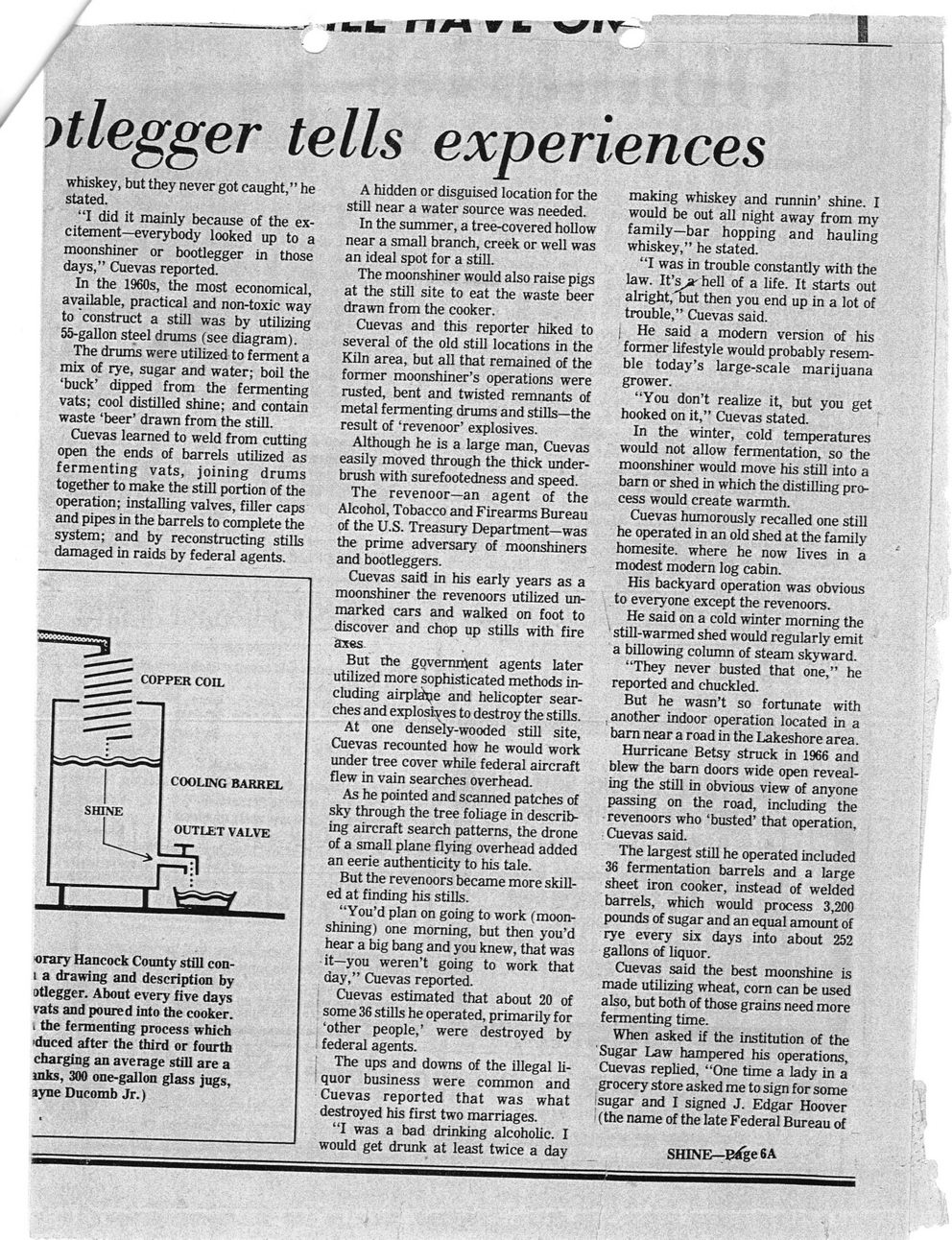

___ ____ .1,1. f MHk V k _| rtlegger tells experiences whiskey, but they never got caught,” he stated. “I did it mainly because of the excitement—everybody looked up to a moonshiner or bootlegger in those days,” Cuevas reported. In the 1960s, the most economical, available, practical and non-toxic way to construct a still was by utilizing 55-gallon steel drums (see diagram). The drums were utilized to ferment a mix of rye, sugar and water; boil the ‘buck’ dipped from the fermenting vats; cool distilled shine; and contain waste ‘beer’ drawn from the still. Cuevas learned to weld from cutting open the ends of barrels utilized as fermenting vats, joining drums together to make the still portion of the operation; installing valves, filler caps and pipes in the barrels to complete the system; and by reconstructing stills damaged in raids by federal agents. orary Hancock County still con-i a drawing and description by atlegger. About every five days vats and poured into the cooker, i the fermenting process which >duced after the third or fourth charging an average still are a inks, 300 one-gallon glass jugs, ayne Ducomb Jr.) A hidden or disguised location for the still near a water source was needed. In the summer, a tree-covered hollow near a small branch, creek or well was an ideal spot for a still. The moonshiner would also raise pigs at the still site to eat the waste beer drawn from the cooker. Cuevas and this reporter hiked to several of the old still locations in the Kiln area, but all that remained of the former moonshiner’s operations were rusted, bent and twisted remnants of metal fermenting drums and stills—the result of ‘revenoor’ explosives. Although he is a large man, Cuevas easily moved through the thick underbrush with surefootedness and speed. The revenoor—an agent of the Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms Bureau of the U.S. Treasury Department—was the prime adversary of moonshiners and bootleggers. Cuevas said in his early years as a moonshiner the revenoors utilized unmarked cars and walked on foot to discover and chop up stills with fire axes But the governrrtent agents later utilized more sophisticated methods including airpldqe and helicopter searches and explosives to destroy the stills. At one densely-wooded still site, Cuevas recounted how he would work under tree cover while federal aircraft flew in vain searches overhead. As he pointed and scanned patches of sky through the tree foliage in describing aircraft search patterns, the drone of a small plane flying overhead added an eerie authenticity to his tale. But the revenoors became more skilled at finding his stills. “You’d plan on going to work (moonshining) one morning, but then you’d hear a big bang and you knew, that was it—you weren’t going to work that day,” Cuevas reported. Cuevas estimated that about 20 of some 36 stills he operated, primarily for ‘other people,’ were destroyed by federal agents. The ups and downs of the illegal liquor business were common and Cuevas reported that was what destroyed his first two marriages. “I was a bad drinking alcoholic. I would get drunk at least twice a day making whiskey and runnin’ shine. I would be out all night away from my family—bar hopping and hauling whiskey,” he stated. “I was in trouble constantly with the law. It’s^SK hell of a life. It starts out alright, but then you end up in a lot of trouble,” Cuevas said. i He said a modern version of his former lifestyle would probably resemble today’s large-scale marijuana grower. “You don’t realize it, but you get hooked on it,” Cuevas stated. In the winter, cold temperatures would not allow fermentation, so the moonshiner would move his still into a barn or shed in which the distilling process would create warmth. Cuevas humorously recalled one still he operated in an old shed at the family homesite. where he now lives in a modest modern log cabin. His backyard operation was obvious to everyone except the revenoors. He said on a cold winter morning the ' still-warmed shed would regularly emit a billowing column of steam skyward. “They never busted that one,” he reported and chuckled. But he wasn’t so fortunate with .another indoor operation located in a barn near a road in the Lakeshore area. Hurricane Betsy struck in 1966 and blew the bam doors wide open revealing the still in obvious view of anyone passing on the road, including the revenoors who ‘busted’ that operation, Cuevas said. The largest still he operated included 36 fermentation barrels and a large sheet iron cooker, instead of welded barrels, which would process 3,200 pounds of sugar and an equal amount of rye every six days into about 252 gallons of liquor. Cuevas said the best moonshine is made utilizing wheat, com can be used also, but both of those grains need more fermenting time. When asked if the institution of the Sugar Law hampered his operations, Cuevas replied, “One time a lady in a grocery store asked me to sign for some i sugar and I signed J. Edgar Hoover (the name of the late Federal Bureau of SHINE—B^ge 6A

Kiln Greg-Cuevas-Kiln-moonshine (2)