This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

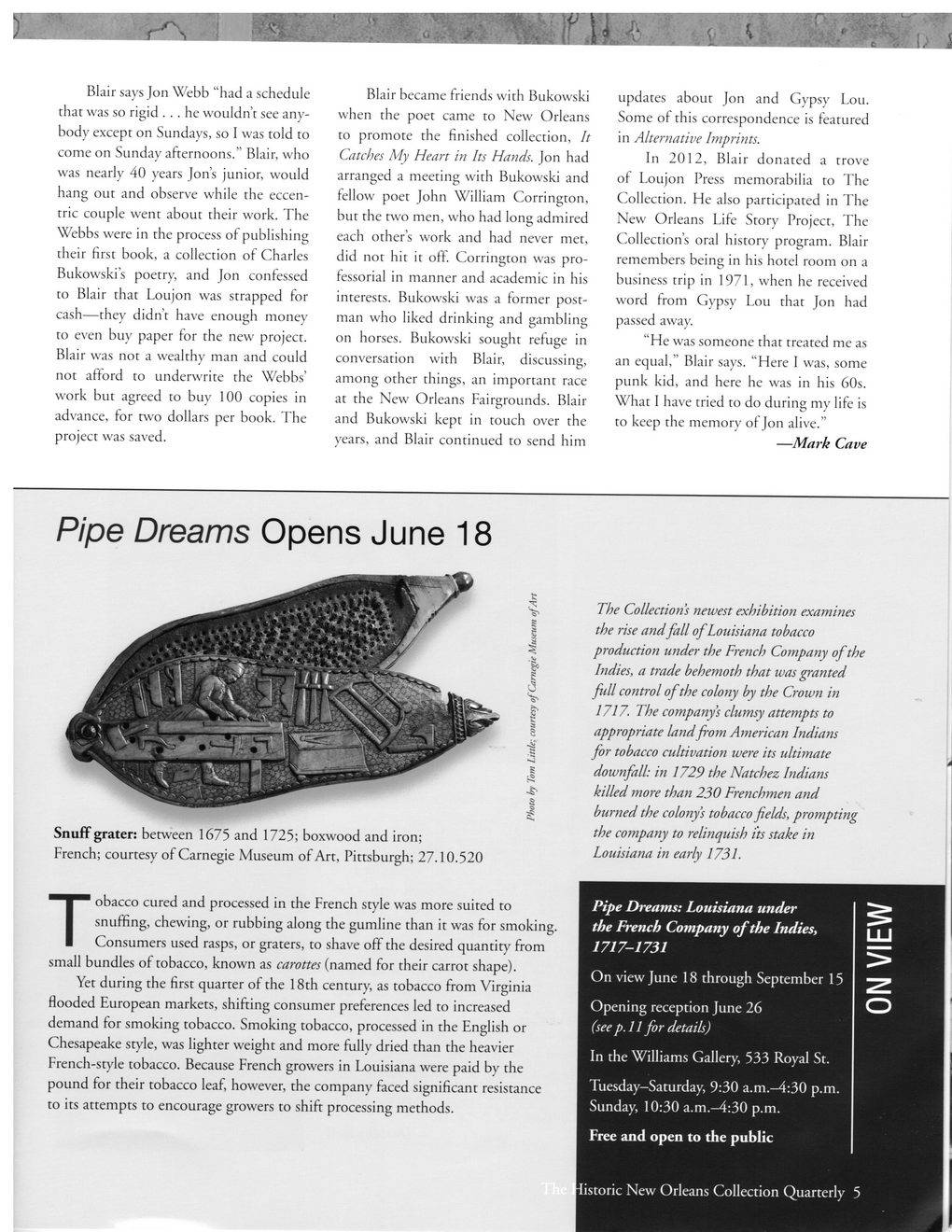

Blair says Jon Webb “had a schedule that was so rigid ... he wouldn’t see anybody except on Sundays, so I was told to come on Sunday afternoons.” Blair, who was nearly 40 years Jon’s junior, would hang out and observe while the eccentric couple went about their work. The Webbs were in the process of publishing their first book, a collection of Charles Bukowski’s poetry, and Jon confessed to Blair that Loujon was strapped for cash—they didn’t have enough money to even buy paper for the new project. Blair was not a wealthy man and could not afford to underwrite the Webbs’ work but agreed to buy 100 copies in advance, for two dollars per book. The project was saved. Blair became friends with Bukowski when the poet came to New Orleans to promote the finished collection, It Catches My Heart in Its Hands. Jon had arranged a meeting with Bukowski and fellow poet John William Corrington, but the two men, who had long admired each other’s work and had never met, did not hit it off. Corrington was professorial in manner and academic in his interests. Bukowski was a former postman who liked drinking and gambling on horses. Bukowski sought refuge in conversation with Blair, discussing, among other things, an important race at the New Orleans Fairgrounds. Blair and Bukowski kept in touch over the years, and Blair continued to send him updates about Jon and Gypsy Lou. Some of this correspondence is featured in Alternative Imprints. In 2012, Blair donated a trove of Loujon Press memorabilia to The Collection. He also participated in The New Orleans Life Story Project, The Collection’s oral history program. Blair remembers being in his hotel room on a business trip in 1971, when he received word from Gypsy Lou that Jon had passed away. “He was someone that treated me as an equal,” Blair says. “Here I was, some punk kid, and here he was in his 60s. What I have tried to do during my life is to keep the memory of Jon alive.” —Mark Cave The Collection’s newest exhibition examines the rise and fall ofLouisiana tobacco production under the French Company of the Indies, a trade behemoth that was granted full control of the colony by the Crown in 1717. The company’s clumsy attempts to appropriate land from American Indians for tobacco cultivation were its ultimate downfall: in 1729 the Natchez Indians killed more than 230 Frenchmen and burned the colony’s tobacco fields, prompting the company to relinquish its stake in Louisiana in early 1731. Pipe Dreams: Louisiana under the French Company of the Indies, 1717-1731 On view June 18 through September 15 Opening reception June 26 (see p. 11 for details) In the Williams Gallery, 533 Royal St. Tuesday—Saturday, 9:30 a.m.—4:30 p.m. Sunday, 10:30 a.m.—4:30 p.m. Free and open to the public Pipe Dreams Opens June 18 Snuff grater: between 1675 and 1725; boxwood and iron; French; courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; 27.10.520 Tobacco cured and processed in the French style was more suited to snuffing, chewing, or rubbing along the gumline than it was for smoking. Consumers used rasps, or graters, to shave off the desired quantity from small bundles of tobacco, known as carottes (named for their carrot shape). Yet during the first quarter of the 18th century, as tobacco from Virginia flooded European markets, shifting consumer preferences led to increased demand for smoking tobacco. Smoking tobacco, processed in the English or Chesapeake style, was lighter weight and more fully dried than the heavier French-style tobacco. Because French growers in Louisiana were paid by the pound for their tobacco leaf, however, the company faced significant resistance to its attempts to encourage growers to shift processing methods. istoric New Orleans Collection Quarterly 5 ON VIEW

New Orleans Quarterly 2013 Summer (05)