This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

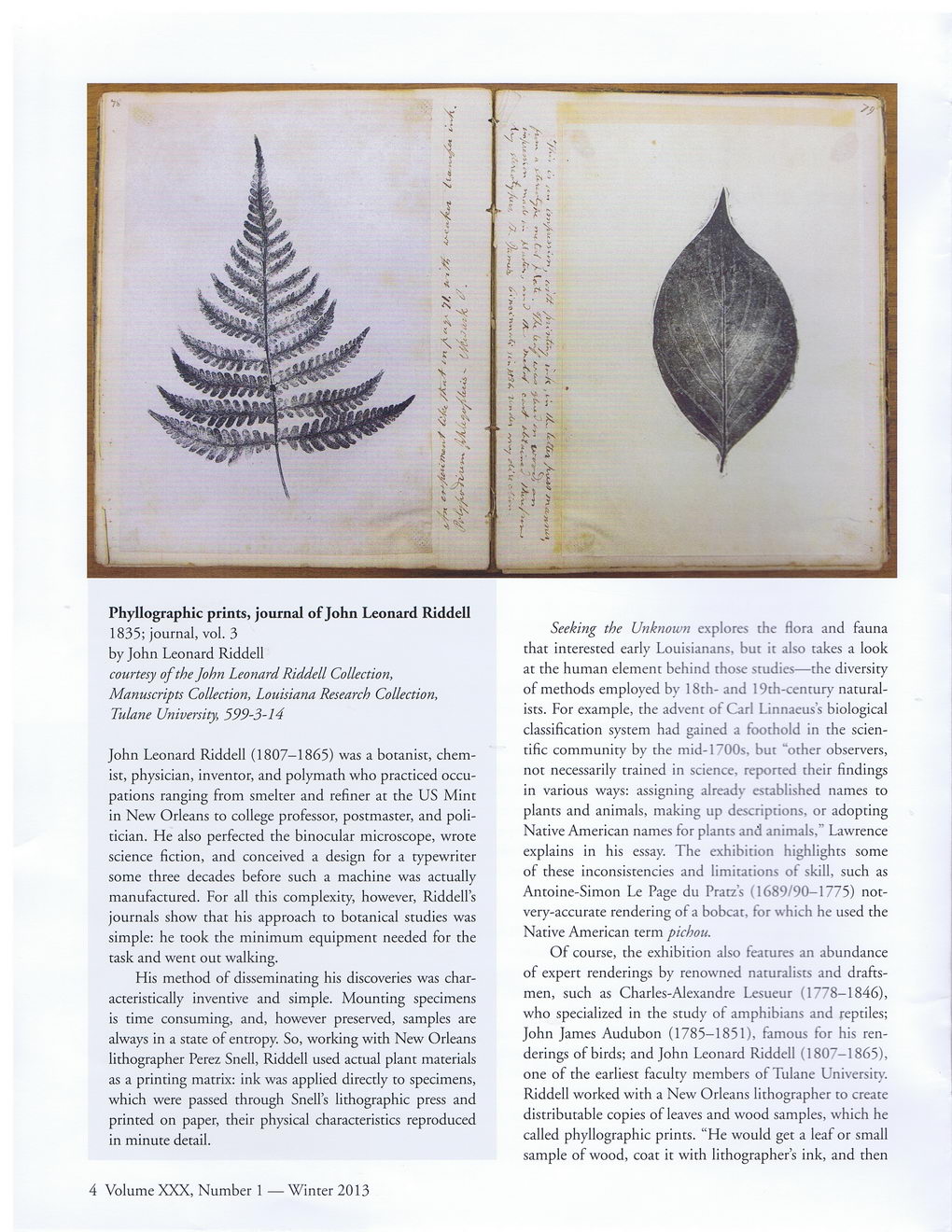

Phyllographic prints, journal of John Leonard Riddell 1835; journal, vol. 3 by John Leonard Riddell courtesy of the John Leonard Riddell Collection, Manuscripts Collection, Louisiana Research Collection, Tulane University, 599-3-14 John Leonard Riddell (1807-1865) was a botanist, chemist, physician, inventor, and polymath who practiced occupations ranging from smelter and refiner at the US Mint in New Orleans to college professor, postmaster, and politician. He also perfected the binocular microscope, wrote science fiction, and conceived a design for a typewriter some three decades before such a machine was actually manufactured. For all this complexity, however, Riddell’s journals show that his approach to botanical studies was simple: he took the minimum equipment needed for the task and went out walking. His method of disseminating his discoveries was characteristically inventive and simple. Mounting specimens is time consuming, and, however preserved, samples are always in a state of entropy. So, working with New Orleans lithographer Perez Snell, Riddell used actual plant materials as a printing matrix: ink was applied directly to specimens, which were passed through Snell’s lithographic press and printed on paper, their physical characteristics reproduced in minute detail. Seeking the Unknown explores the flora and fauna that interested early Louisianans, but it also takes a look at the human element behind those studies—the diversity of methods employed by 18th- and 19th-century naturalists. For example, the advent of Carl Linnaeus’s biological classification system had gained a foothold in the scientific community by the mid-1700s, but “other observers, not necessarily trained in science, reported their findings in various ways: assigning already established names to plants and animals, making up descriptions, or adopting Native American names for plants and animals,” Lawrence explains in his essay. The exhibition highlights some of these inconsistencies and limitations of skill, such as Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz’s (1689/90—1775) not-very-accurate rendering of a bobcat, for which he used the Native American term pichou. Of course, the exhibition also features an abundance of expert renderings by renowned naturalists and draftsmen, such as Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1778-1846), who specialized in the study of amphibians and reptiles; John James Audubon (1785-1851), famous for his renderings of birds; and John Leonard Riddell (1807—1865), one of the earliest faculty members of Tulane University. Riddell worked with a New Orleans lithographer to create distributable copies of leaves and wood samples, which he called phyllographic prints. “He would get a leaf or small sample of wood, coat it with lithographer’s ink, and then 4 Volume XXX, Number 1 —Winter 2013

New Orleans Quarterly 2013 Winter (04)