This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

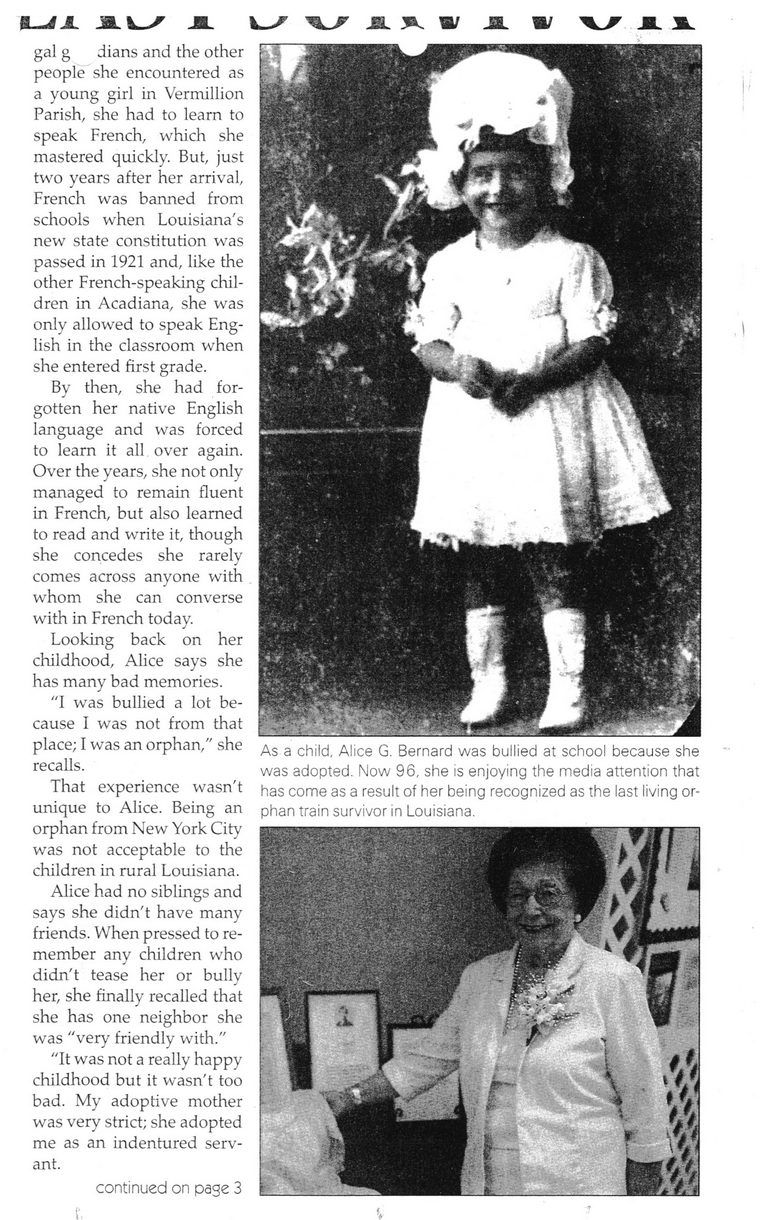

tt—rf JL A Ly JL Ly JL W J3L W JL JL gal g dians and the other people she encountered as a young girl in Vermillion Parish, she had to learn to speak French, which she mastered quickly. But, just two years after her arrival, French was banned from schools when Louisiana's new state constitution was passed in 1921 and, like the other French-speaking children in Acadiana, she was only allowed to speak English in the classroom when she entered first grade. By then, she had forgotten her native English language and was forced to learn it all over again. Over the years, she not only managed to remain fluent in French, but also learned to read and write it, though she concedes she rarely comes across anyone with whom she can converse with in French today. Looking back on her childhood, Alice says she has many bad memories. "I wTas bullied a lot because I was not from that place; I was an orphan," she recalls. That experience wasn't unique to Alice. Being an orphan from New York City was not acceptable to the children in rural Louisiana. Alice had no siblings and says she didn't have many friends. When pressed to remember any children who didn't tease her or bully her, she finally recalled that she has one neighbor she was "very friendly with." "It was not a really happy childhood but it wasn't too bad. My adoptive mother was very strict; she adopted me as an indentured servant. continued on page 3 As a child, Alice G. Bernard was bullied at school because she was adopted. Now 96, she is enjoying the media attention that has come as a result of her being recognized as the last living orphan train survivor in Louisiana.

Orphan Train Riders of BSL Document (157)