This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

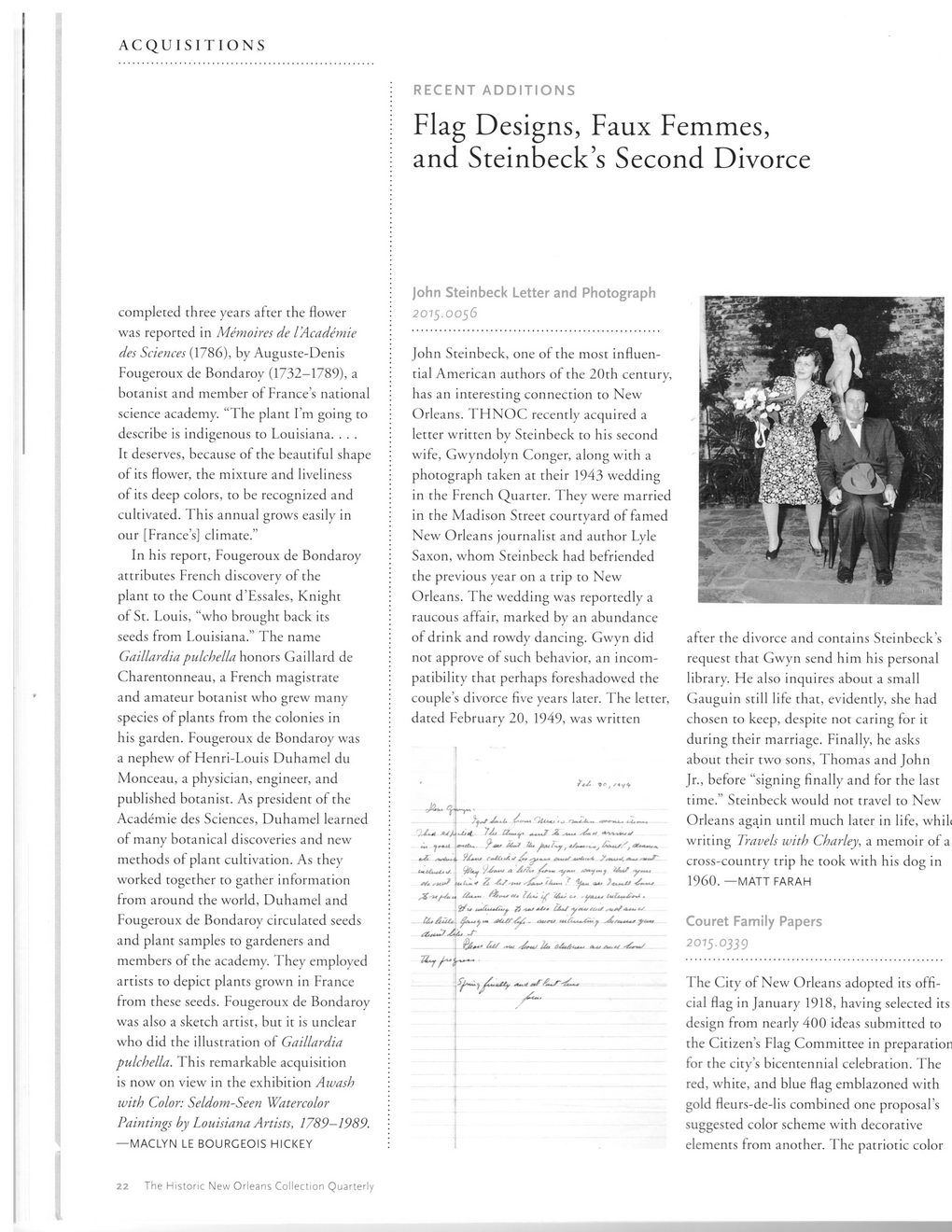

ACQUISITIONS RECENT ADDITIONS Flag Designs, Faux Femmes, and Steinbeck’s Second Divorce completed three years after the flower was reported in Memoires de lAcademie des Sciences (1786), by Auguste-Denis Fougeroux de Bondaroy (1732-1789), a botanist and member of France’s national science academy. “The plant I’m going to describe is indigenous to Louisiana. . . . It deserves, because of the beautiful shape of its flower, the mixture and liveliness of its deep colors, to be recognized and cultivated. This annual grows easily in our [France’s] climate.” In his report, Fougeroux de Bondaroy attributes French discovery of the plant to the Count d’Essales, Knight of St. Louis, “who brought back its seeds from Louisiana.” The name Gaillardia pulchella honors Gaillard de Charentonneau, a French magistrate and amateur botanist who grew manv species of plants from the colonies in his garden. Fougeroux de Bondaroy was a nephew of Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau, a physician, engineer, and published botanist. As president of the Academie des Sciences, Duhamel learned of many botanical discoveries and new methods of plant cultivation. As they worked together to gather information from around the world, Duhamel and Fougeroux de Bondaroy circulated seeds and plant samples to gardeners and members of the academy. They employed artists to depict plants grown in France from these seeds. Fougeroux de Bondaroy was also a sketch artist, but it is unclear who did the illustration of Gaillardia pulchella. This remarkable acquisition is now on view in the exhibition Awash with Color: Seldom-Seen Watercolor Paintings by Louisiana Artists, 1789—1989. — MACLYN LE BOURGEOIS HICKEY john Steinbeck Letter and Photograph 2015.0056 John Steinbeck, one of the most influential American authors of the 20th century, has an interesting connection to New Orleans. THNOC recently acquired a letter written by Steinbeck to his second wife, Gwyndolyn Conger, along with a photograph taken at their 1943 wedding in the French Quarter. They were married in the Madison Street courtyard of famed New Orleans journalist and author Lyle Saxon, whom Steinbeck had befriended the previous year on a trip to New Orleans. The wedding was reportedly a raucous affair, marked by an abundance of drink and rowdy dancing. Gwyn did not approve of such behavior, an incompatibility that perhaps foreshadowed the couple’s divorce five years later. The letter, dated February 20, 1949, was written /Wu, ,^*4 *4)* »&«< (7*«uy» /lu a -y. CZj&uU, j ljk»' J .<*■ AtiS 74m* l* .ymitf l !-U isj i«i1 mf /Lr*?»■« • /-■ after the divorce and contains Steinbeck’s request that Gwyn send him his personal library. He also inquires about a small Gauguin still life that, evidently, she had chosen to keep, despite not caring for it during their marriage. Finally, he asks about their two sons, Thomas and John Jr., before “signing finally and for the last time.” Steinbeck would not travel to New Orleans again until much later in life, whili writing Travels with Charley, a memoir of a cross-country trip he took with his dog in I960. —MATT FARAH Couret Family Papers 2015.0339 The City of New Orleans adopted its official flag in January 1918, having selected its design from nearly 400 ideas submitted to the Citizen’s Flag Committee in preparation for the city’s bicentennial celebration. The red, white, and blue flag emblazoned with gold fleurs-de-lis combined one proposal’s suggested color scheme with decorative elements from another. The patriotic color 22 The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly

New Orleans Quarterly 2016 Spring (22)