This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

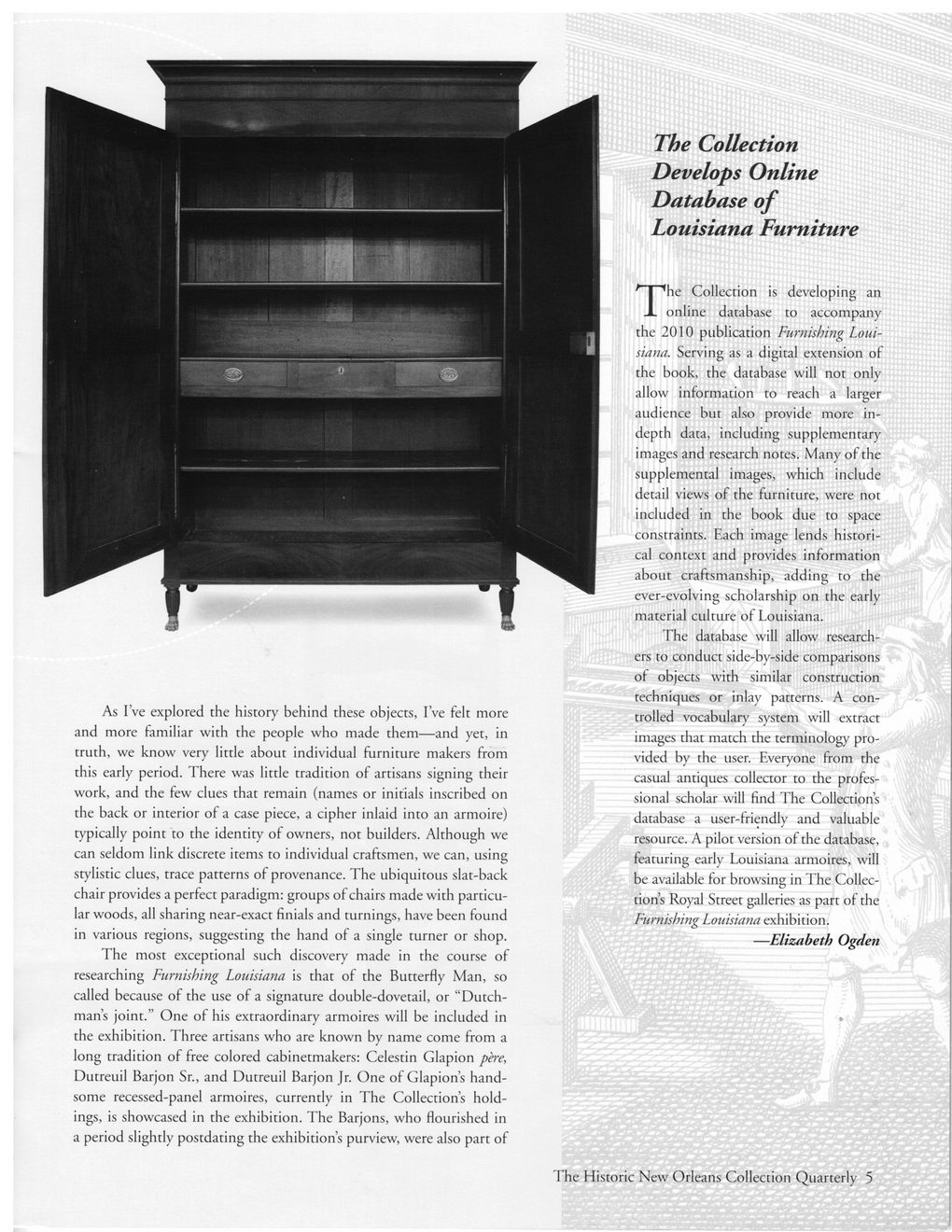

As I’ve explored the history behind these objects, I’ve felt more and more familiar with the people who made them—and yet, in truth, we know very little about individual furniture makers from this early period. There was little tradition of artisans signing their work, and the few clues that remain (names or initials inscribed on the back or interior of a case piece, a cipher inlaid into an armoire) typically point to the identity of owners, not builders. Although we can seldom link discrete items to individual craftsmen, we can, using stylistic clues, trace patterns of provenance. The ubiquitous slat-back chair provides a perfect paradigm: groups of chairs made with particular woods, all sharing near-exact finials and turnings, have been found in various regions, suggesting the hand of a single turner or shop. The most exceptional such discovery made in the course of researching Furnishing Louisiana is that of the Butterfly Man, so called because of the use of a signature double-dovetail, or “Dutchman’s joint.” One of his extraordinary armoires will be included in the exhibition. Three artisans who are known by name come from a long tradition of free colored cabinetmakers: Celestin Glapion pere, Dutreuil Barjon Sr., and Dutreuil Barjon Jr. One of Glapion’s handsome recessed-panel armoires, currently in The Collection’s holdings, is showcased in the exhibition. The Barjons, who flourished in a period slightly postdating the exhibition’s purview, were also part of The Collection Develops Online Database of Louisiana Furniture The Collection is developing an online database to accompany the 2010 publication Furnishing Louisiana. Serving as a digital extension of the book, the database will not only allow information to reach a larger audience but also provide more in-depth data, including supplementary images and research notes. Many of the supplemental images, which include detail views of the furniture, were not included in the book due to space constraints. Each image lends historical context and provides information about craftsmanship, adding to the ever-evolving scholarship on the early material culture of Louisiana. The database will allow researchers to conduct side-by-side comparisons of objects with similar construction techniques or inlay patterns. A controlled vocabulary system will extract images that match the terminology provided by the user. Everyone from the casual antiques collector to the professional scholar will find The Collections database a user-friendly and valuable resource. A pilot version of the database, featuring early Louisiana armoires, will be available for browsing in The Collection’s Royal Street galleries as part of the Furnishing Louisiana exhibition. —Elizabeth Ogden The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly 5

New Orleans Quarterly 2012 Winter (05)