This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

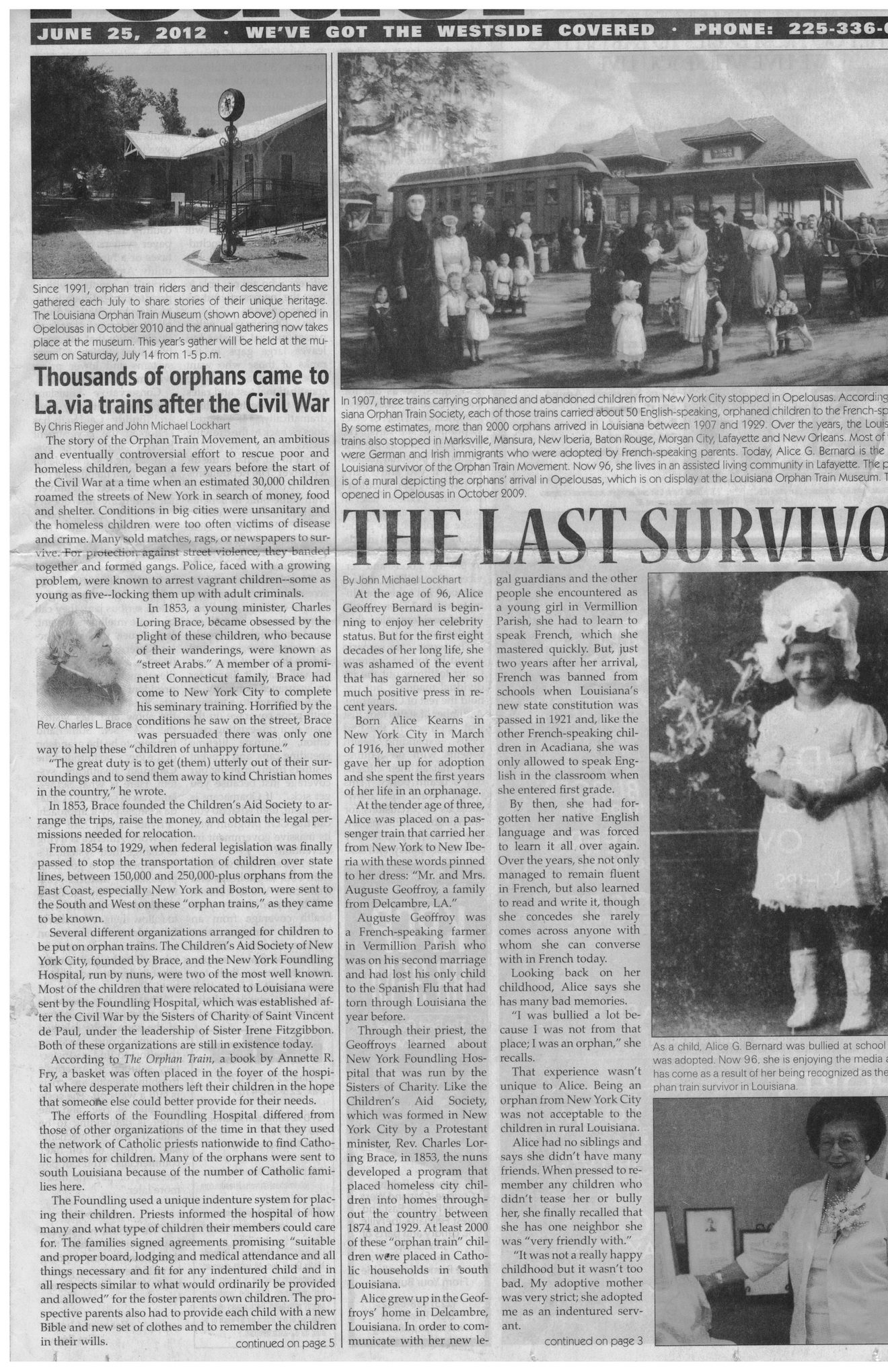

JUNE 25, 2012 • WE'VE GOT THE WESTSIPE COVERED y PHONEs 225-336- Since 1991, orphan train riders and their descendants have gathered each July to share stories of their unique heritage. The Louisiana Orphan Train Museum (shown above) opened in Opelousas in October 2010 and the annual gathering now takes place at the museum. This year’s gather will be held at the museum on Saturday, July 14 from 1-5 p.m. Thousands of orphans came to La. via trains after the Civil War By Chris Rieger and John Michael Lockhart The story of the Orphan Train Movement, an ambitious and eventually controversial effort to rescue poor and homeless children, began a few years before the start of the Civil War at a time when an estimated 30,000 children roamed the streets of New York in search of money, food and shelter. Conditions in big cities were unsanitary and the homeless children were too often victims of disease and crime. Many sold matches, rags, or newspapers to survive. -Fnr protectknr-a^ainst street ^otencerthtrr-banded together and formed gangs. Police, faced with a growing problem, were known to arrest vagrant children—some as young as five—locking them up with adult criminals. In 1853, a young minister, Charles Loring Brace, became obsessed by the ■ , * plight of these children, who because of their wanderings, were known as "street Arabs." A member of a prominent Connecticut family, Brace had come to New York City to complete his seminary training. Horrified by the Rev Charles L Brace conditions he saw on the street, Brace was persuaded there was only one way to help these "children of unhappy fortune." "The great duty is to get (them) utterly out of their surroundings and to send them away to kind Christian homes in the country," he wrote. In 1853, Brace founded the Children's Aid Society to arrange the trips, raise the money, and obtain the legal permissions needed for relocation. From 1854 to 1929, when federal legislation was finally passed to stop the transportation of children over state lines, between 150,000 and 250,000-plus orphans from the East Coast, especially New York and Boston, were sent to the South and West on these "orphan trains," as they came to be known. Several different organizations arranged for children to be put on orphan trains. The Children's Aid Society of New York City, founded by Brace, and the New York Foundling Hospital, run by nuns, were two of the most well known. Most of the children that were relocated to Louisiana were sent by the Foundling Hospital, which was established after the Civil War by the Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul, under the leadership of Sister Irene Fitzgibbon. Both of these organizations are still in existence today. According to The Orphan Train, a book by Annette R. Fry, a basket was often placed in the foyer of the hospital where desperate mothers left their children in the hope that someof»e else could better provide for their needs. The efforts of the Foundling Hospital differed from those of other organizations of the time in that they used the network of Catholic priests nationwide to find Catholic homes for children. Many of the orphans were sent to south Louisiana because of the number of Catholic families here. The Foundling used a unique indenture system for placing their children. Priests informed the hospital of how many and what type of children their members could care for. The families signed agreements promising "suitable and proper board, lodging and medical attendance and all things necessary and fit for any indentured child and in all respects similar to what would ordinarily be provided and allowed" for the foster parents own children. The prospective parents also had to provide each child with a new Bible and new set of clothes and to remember the children in their wills. continued on page 5 In 1907, three trains carrying orphaned and abandoned children from New York City stopped in Opelousas. According siana Orphan Train Society, each of those trains carried about 50 English-speaking, orphaned children to the French-sp By some estimates, more than 2000 orphans arrived in Louisiana between 1907 and 1929. Over the years, the Louis trains also stopped in Marksville, Mansura, New Iberia, Baton Rouge, Morgan City, Lafayette and New Orleans. Most of ■ were German and Irish immigrants who were adopted by French-speaking parents. Today, Alice G. Bernard is the Louisiana survivor of the Orphan Train Movement. Now 96, she lives in an assisted living community in Lafayette. The p is of a mural depicting the orphans' arrival in Opelousas, which is on display at the Louisiana Orphan Train Museum. T opened in Opelousas in October 2009. gal guardians and the other people she encountered as a young girl in Vermillion Parish, she had to learn to speak French, which she mastered quickly. But, just two years after her arrival, French was banned from schools when Louisiana's new state constitution was passed in 1921 and, like the other French-speaking children in Acadiana, she was only allowed to speak English in the classroom when she entered first grade. By then, she had forgotten her native English language and was forced to learn it all over again. Over the years, she not only managed to remain fluent in French, but also learned to read and write it, though she concedes she rarely comes across anyone with whom she can converse with in French today. Looking back on her childhood, Alice says she has many bad memories. "I was bullied a lot because I was not from that place; I was an orphan," she recalls. That experience wasn't unique to Alice. Being an orphan from New York City was not acceptable to the children in rural Louisiana. Alice had no siblings and says she didn't have many friends. When pressed to remember any children who didn't tease her or bully her, she finally recalled that she has one neighbor she was "very friendly with." "It was not a really happy childhood but it wasn't too bad. My adoptive mother was very strict; she adopted me as an indentured servant. continued on page 3 By John Michael Lockhart At the age of 96, Alice Geoffrey Bernard is beginning to enjoy her celebrity status. But for the first eight decades of her long life, she was ashamed of the event that has garnered her so much positive press in recent years. Born Alice Kearns in New York City in March of 1916, her unwed mother gave her up for adoption and she spent the first years of her life in an orphanage. At the tender age of three, Alice was placed on a passenger train that carried her from New York to New Iberia with these words pinned to her dress: "Mr. and Mrs. Auguste Geoffroy, a family from Delcambre, LA." Auguste Geoffroy was a French-speaking farmer in Vermillion Parish who was on his second marriage and had lost his only child to the Spanish Flu that had torn through Louisiana the year before. Through their priest, the Geoffreys learned about New York Foundling Hospital that was run by the Sisters of Charity. Like the Children's Aid Society, which was formed in New York City by a Protestant minister, Rev. Charles Loring Brace, in 1853, the nuns developed a program that placed homeless city children into homes throughout the country between 1874 and 1929. At least 2000 of these "orphan train" children were placed in Catholic households in south Louisiana. Alice grew up in the Geoffreys' home in Delcambre, Louisiana. In order to communicate with her new le- As a child. Alice G. Bernard was bullied at school was adopted. Now 96, she is enjoying the media ; has come as a result of her being recognized as the phan train survivor in Louisiana.

Orphan Train Riders of BSL Document (006)