This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

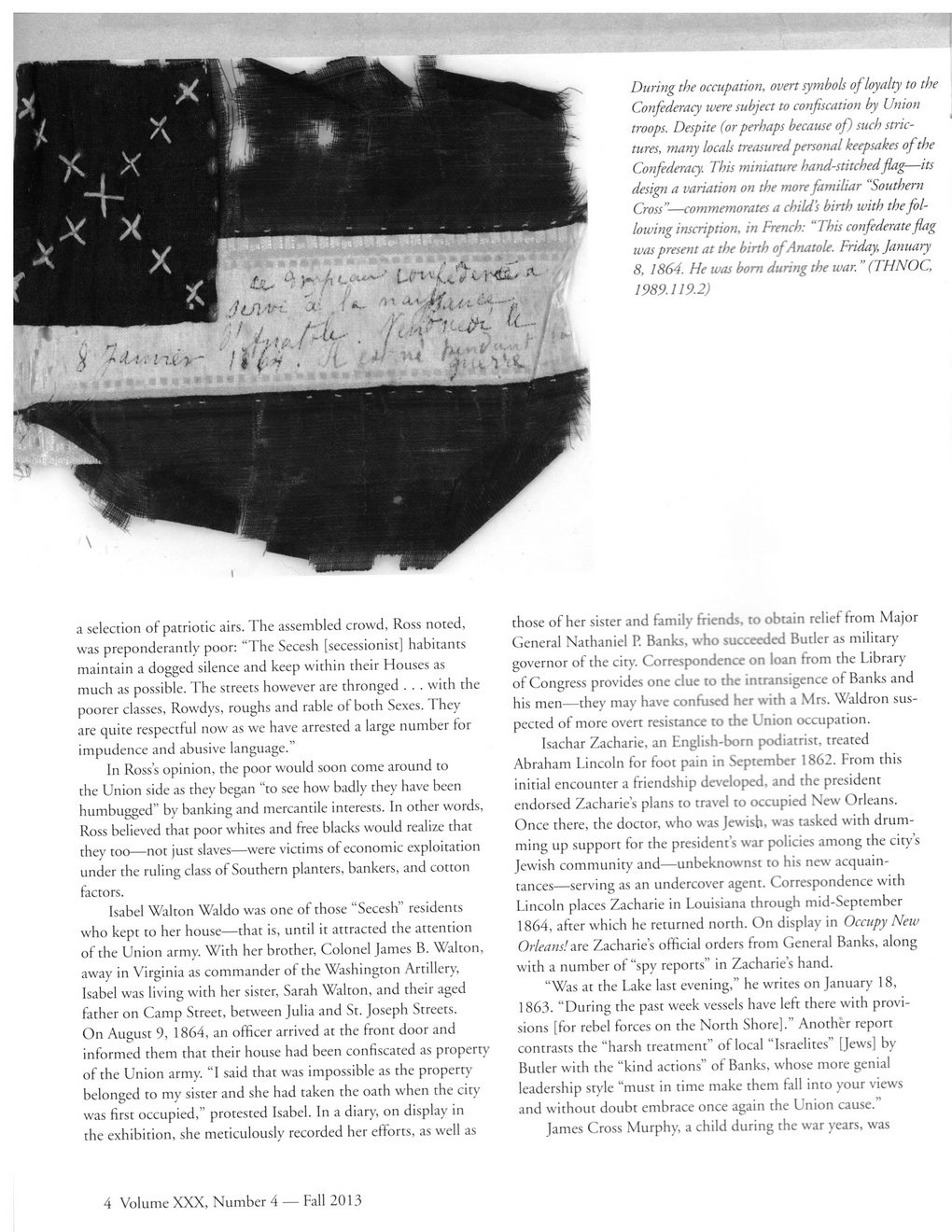

V 7.t >- tr /| <_ Ox.***- ^ v ^ ^ *'»• ■ Jtjl-v-t x 1 *- -M '! U, /--^ . - /»'/*: ! ^ ■' h, ivx During the occupation, otrrr symbols of loyalty to the Confederacy were subject to confiscation by Union troops. Despite (orperhaps because of) such strictures, many locals treasured personal keepsakes of the Confederacy. This miniature hand-stitchedflag—its design a variation on the more familiar “Southern Cross”—commemorates a child's birth with the following inscription, in French: “This confederate flag was present at the birth of Anatole. Friday, January 8, 1864. He was bom during the war. ” (THNOC, 1989.119.2) a selection of patriotic airs. The assembled crowd, Ross noted, was preponderantly poor: “The Secesh [secessionist] habitants maintain a dogged silence and keep within their Houses as much as possible. The streets however are thronged . . . with the poorer classes, Rowdys, roughs and rable of both Sexes. They are quite respectful now as we have arrested a large number for impudence and abusive language.” In Ross’s opinion, the poor would soon come around to the Union side as they began “to see how badly they have been humbugged” by banking and mercantile interests. In other words, Ross believed that poor whites and free blacks would realize that they too—not just slaves—were victims of economic exploitation under the ruling class of Southern planters, bankers, and cotton factors. Isabel Walton Waldo was one of those “Secesh” residents who kept to her house—that is, until it attracted the attention of the Union army. With her brother, Colonel James B. Walton, away in Virginia as commander of the Washington Artillery, Isabel was living with her sister, Sarah Walton, and their aged father on Camp Street, between Julia and St. Joseph Streets. On August 9, 1864, an officer arrived at the front door and informed them that their house had been confiscated as property of the Union army. “I said that was impossible as the property belonged to my sister and she had taken the oath when the city was first occupied,” protested Isabel. In a diary, on display in the exhibition, she meticulously recorded her efforts, as well as those of her sister and family friends, to obtain relief from Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, who succecded Butler as military governor of the city. Correspondence on loan from the Library of Congress provides one clue to the intransigence of Banks and his men—they may have confused her with a Mrs. Waldron suspected of more overt resistance to the Union occupation. Isachar Zacharie, an English-born podiatrist, treated Abraham Lincoln for foot pain in September 1862. From this initial encounter a friendship developed, and the president endorsed Zacharies plans to travel to occupied New Orleans. Once there, the doctor, who was Jewish, was tasked with drumming up support for the presidents war policies among the city’s Jewish community and—unbeknownst to his new acquaintances—serving as an undercover agent. Correspondence with Lincoln places Zacharie in Louisiana through mid-September 1864, after which he returned north. On display in Occupy New Orleans!we Zacharies official orders from General Banks, along with a number of “spy reports” in Zacharies hand. “Was at the Lake last evening,” he writes on January 18, 1863. “During the past week vessels have left there with provisions [for rebel forces on the North Shore].” Another report contrasts the “harsh treatment” of local “Israelites” [Jews] by Butler with the “kind actions” of Banks, whose more genial leadership style “must in time make them fall into your views and without doubt embrace once again the Union cause.” James Cross Murphy, a child during the war years, was 4 Volume XXX, Number 4 — Fall 2013

New Orleans Quarterly 2013 Fall (04)