This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

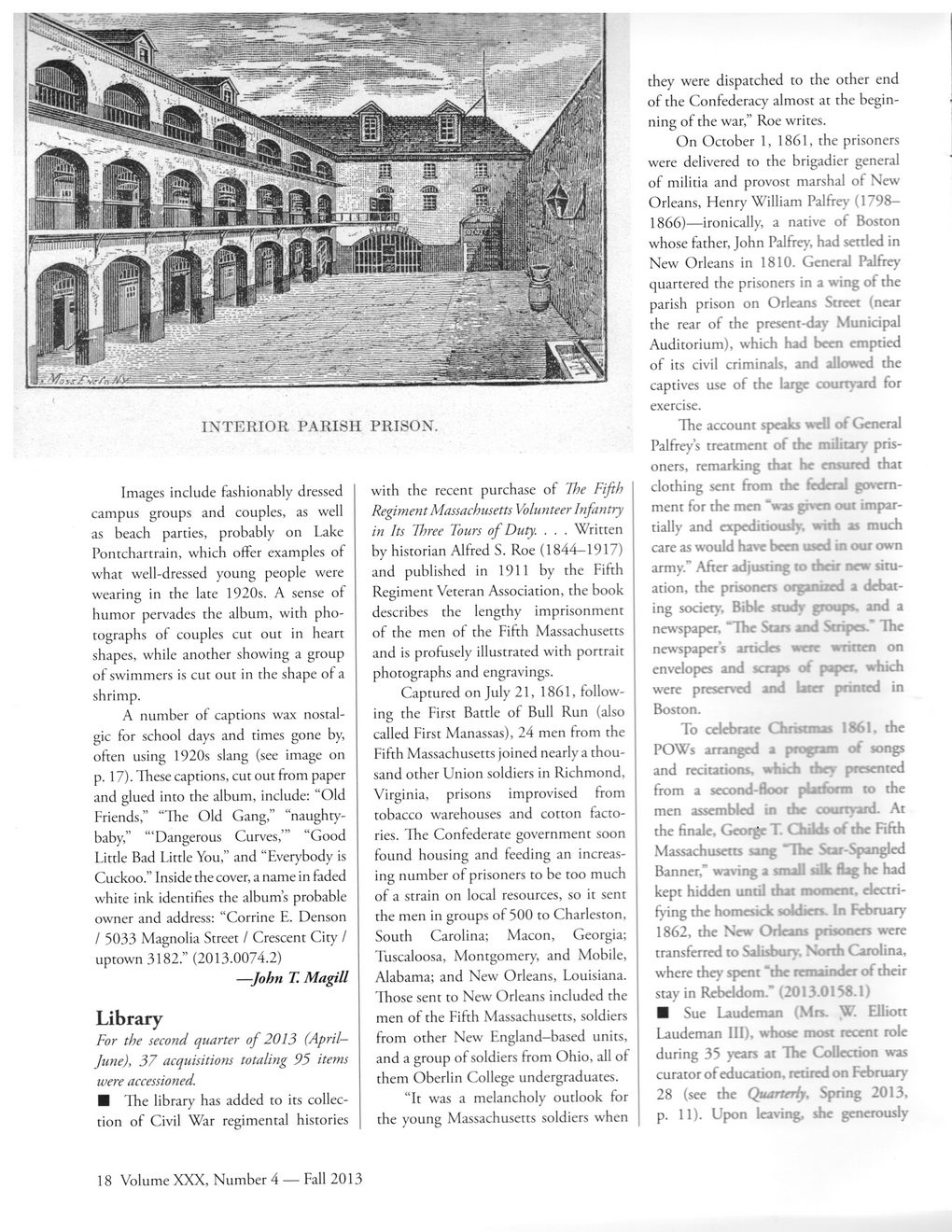

Images include fashionably dressed campus groups and couples, as well as beach parties, probably on Lake Pontchartrain, which offer examples of what well-dressed young people were wearing in the late 1920s. A sense of humor pervades the album, with photographs of couples cut out in heart shapes, while another showing a group of swimmers is cut out in the shape of a shrimp. A number of captions wax nostalgic for school days and times gone by, often using 1920s slang (see image on p. 17). These captions, cut out from paper and glued into the album, include: “Old Friends,” “The Old Gang,” “naughty-baby,” ‘“Dangerous Curves,’” “Good Little Bad Little You,” and “Everybody is Cuckoo.” Inside the cover, a name in faded white ink identifies the album’s probable owner and address: “Corrine E. Denson / 5033 Magnolia Street / Crescent City / uptown 3182.” (2013.0074.2) —John T. Magill Library For the second quarter of 2013 (April— June), 37 acquisitions totaling 95 items were accessioned. M The library has added to its collection of Civil War regimental histories with the recent purchase of The Fifth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in Its Three Tours of Duty. . . . Written by historian Alfred S. Roe (1844-1917) and published in 1911 by the Fifth Regiment Veteran Association, the book describes the lengthy imprisonment of the men of the Fifth Massachusetts and is profusely illustrated with portrait photographs and engravings. Captured on July 21, 1861, following the First Battle of Bull Run (also called First Manassas), 24 men from the Fifth Massachusetts joined nearly a thousand other Union soldiers in Richmond, Virginia, prisons improvised from tobacco warehouses and cotton factories. The Confederate government soon found housing and feeding an increasing number of prisoners to be too much of a strain on local resources, so it sent the men in groups of 500 to Charleston, South Carolina; Macon, Georgia; Tuscaloosa, Montgomery, and Mobile, Alabama; and New Orleans, Louisiana. Those sent to New Orleans included the men of the Fifth Massachusetts, soldiers from other New England-based units, and a group of soldiers from Ohio, all of them Oberlin College undergraduates. “It was a melancholy outlook for the young Massachusetts soldiers when they were dispatched to the other end of the Confederacy almost at the beginning of the war,” Roe writes. On October 1, 1861, the prisoners were delivered to the brigadier general of militia and provost marshal of New Orleans, Henry William Palfrey (1798— 1866)—ironically, a native of Boston whose father, John Palfrey, had settled in New Orleans in 1810. General Palfrey quartered the prisoners in a wing of the parish prison on Orleans Street (near the rear of the present-day Municipal Auditorium), which had been emptied of its civil criminals, and allowed the captives use of the large courtyard for exercise. The account speaks well of General Palfreys treatment of the military prisoners, remarking that he ensured that clothing sent from the federal government for the men "was ghxn out impartially and expeditiously, with as much care as would have been used in our own army.” After adjusting to their cew situation, the prisoners organized a debating society, Bible study groups, and a newspaper, “The Stan and Scripcs.* The newspapers articles were written on envelopes and scraps of paper, which were preserved and bier printed in Boston. To celebrate Christmas 1861, the POWs arranged a program of songs and recitations, which they presented from a second-floor pbribcm to the men assembled in the courtyard. At the finale, George T. Childs of the Fifth Massachusetts sang “The Scar-Spangled Banner,” waving a small silk flag he had kept hidden until that moment, electrifying the homesick soldiers. In February 1862, the New Orleans prisoners were transferred to Salisbury. North Carolina, where they spent “the remainder of their stay in Rebddom." (2013.0158.1) ■ Sue Laudeman (Mrs. W. Elliott Laudeman III), whose most recent role during 35 years at The Collection was curator of education, retired on February 28 (see the Quarterly, Spring 2013, p. 11). Upon leaving, she generously 18 Volume XXX, Number 4 — Fall 2013

New Orleans Quarterly 2013 Fall (18)