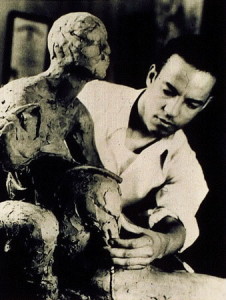

“All my life I have been interested in trying to capture the spiritual quality I see in people, and I feel that the human figure as God made it, is the best means of expressing this spirit in man.”

—Richmond Barthé

A key figure in the Harlem Renaissance during the 1930’s, Richmond Barthé (1901—1989) was a man who endured and triumphed as he followed his own star, a star that led him to many parts of the world in search of opportunities to express the creative vision that marked his presence in this life and, according to Barthé, preceding lives.

A key figure in the Harlem Renaissance during the 1930’s, Richmond Barthé (1901—1989) was a man who endured and triumphed as he followed his own star, a star that led him to many parts of the world in search of opportunities to express the creative vision that marked his presence in this life and, according to Barthé, preceding lives.

Barthé often referred to himself as an “Old Soul” who had been here before. In discussing his belief in reincarnation, he insisted that during an earlier life he was an artist who lived in Egypt.

He believed that he was an artist in each earlier life and that he would always be an artist. He often wondered how else he could have accumulated the experiences and skills that he displayed in his more recently completed life.

Born in Bay Saint Louis, MS, Barthé is a native son whose statues in marble, bronze, and stone are in museums and private collections in France, England, Germany, India, and a half-dozen other foreign countries. His works are permanently displayed in the Metropolitan Museum and the Whitney Museum in New York as well as many other major museums in the United States. His great American eagle is used at the entrance of the Social Security Building in Washington, D. C.

Barthé won two Julius Rosenwald Fellowships and two Guggenheim Fellowships on merit alone. He holds the Audubon Artist Medal of Honor and numerous awards and citations from the American and National Academy of Arts and Letters. In addition he received awards for interracial justice and honorary degrees from Xavier and St. Francis Universities. He also received the Audubon Artists Gold Medal in 1950.

With two honorary art degrees, he once said that he didn’t get to high school because his mother was a widow and he was taken out of the seventh grade to help support the family. Mrs. Marie Raboteau Barthé, his mother, was a seamstress, and when her son was small, she often put him on the floor with pencil and paper while she was at her tasks.

As he grew, beauty and form always attracted him. His pockets held pretty bits of broken glass, sea shells, or a dried leaf of unusual shape, and his one ambition was to be a painter, not a sculptor.

During the summer months and on weekends, he worked for the Harry S. Pond family who had a summer home on the corner of South Beach Boulevard and Ballentine Street in Bay Saint Louis. In 1917 when he was sixteen years old, he went to New Orleans with them as a butler, and the family gave him his first oil paints for a Christmas gift.

“I had never seen an artist at work,” Barthé remarked, “and didn’t even know how to apply oils to canvas.” He learned composition by copying old masters from a volume of reproductions which cost him a hard-earned $25.00.

Lyle Saxon, author of Fabulous New Orleans, discovered his work and encouraged him by posing and then criticizing the result. Occasionally Saxon sent him to the Delgado Art Museum [now the New Orleans Museum of Art] with a note, and these few occasions gave Barthé his first opportunity to see good original pictures.

Barthé’s first exhibit was at a church festival in New Orleans. His life-size painting of the Head of Christ so impressed Father Harry Kane of Blessed Sacrament Parish that he helped Barthé study at the Chicago Art Institute.

His first attempt at sculpture was in 1928 when he modeled the heads of two friends just as an experiment. He was requested to exhibit these in a Chicago art exhibit called “The Negro in Art.” These were reproduced on a New York magazine cover, and Barthé was on his road to fame as a sculptor

In February 1929, following his graduation from The Art Institute of Chicago, Barthé moved to New York, where he began to rise to stardom as a sculptor. During the next two decades, he would build a reputation that would prove to be the envy of many of his peers. The 1930’s and ‘40’s would see him rise to great prominence. No other sculptor in the United States during this period received higher praise for his work by critics and more visibility in the New York press.

In New York, Barthé established his first studio in Harlem. He began to fraternize with writers, dancers, and theater personalities soon after he arrived in New York. His reputation as a sculptor was generally known in Harlem and was acclaimed by philosopher/art critic Alain Locke, who praised his sculpture and regarded it as fresh and vibrant.

The theater had long interested Barthé, and some of his best known works were in this field. As his commissions of theater personalities increased, he decided to move his studio from Harlem to a larger, more comfortable space downtown. One New York critic said that Barthé had the entire New York theater to himself as a sculptor. His model of Katherine Cornell as “Juliet” is in a private collection in Argentina, and he modeled Sir Lawrence Olivier, Dame Judith Anderson, Sir John Gielgud, Maurice Evans, and Gypsy Rose Lee among others.

Although his stated reason for moving downtown was motivated by his need to be accessible to his clients, another reason was that he loved the theater and wanted to be in the company of the stars of the “legitimate” theater. Living downtown also made Barthé more available for invitations and free tickets to theater and dance performances.

Barthé once remarked, “My work is finished mentally before I ever go to the material.” He had a photographic memory and rarely asked an actor to pose. He preferred to study his subjects night after night from a chair in the orchestra during the performance. He believed an actor lived on the stage, but in the studio he was likely to become wooden.

In New York, Barthé experienced success after success. He was considered by writers and critics as one of the leading “moderns” of this time. However, the busy, tense environment in which he found himself took its toll, and he decided to abandon his life of fame at the peak of his career and move to Jamaica. Here he remained for twenty productive years. Away from the limelight, he was in a place that, although distant from his beloved Bay Saint Louis, reminded him of the place of his childhood. There he could commune with nature and experience the beauty of the land.

In the mid-1960’s he left Jamaica and spent the next five years of his life in Switzerland, Spain, and Italy before settling in Pasadena, California. During his last years he thought of returning to painting but instead worked on his memoirs and resumed his communication with his friends in nature—the birds, bees, and other living creatures that he could trust.

Unfortunately these last years of Barthé’s life in Pasadena were quite bleak. Art had brought him fame and prominence, but being the fickle mistress it can be, it had brought him little financial security. Nonetheless, his art caught the eye of actor James Garner, who became a close friend of Barthé and a great admirer of his work. Garner helped Barthé financially; to repay the actor’s generosity, Barthé sculpted a bust of Garner, believed to be the artist’s final work.

The significance of the art and life of Richmond Barthé establishes a chapter in the history of art in America. His poise, dignity, intelligence, and esthetic sensibility are all reflected in the timeless monuments that he has left for our enjoyment and appreciation. These monuments, Barthé’s sculptures, are from the heart, mind, and spirit of a man who endured and who triumphed as he followed his own star.

SOURCES:

“Barthé, Richmond.” Wikipedia. 29 May 2008 14 pars. 22 May 2008.

Golus, Carrie. “Barthé, Richmond 1901-1989.” Contemporary Black Biography. 1977. En- cyclopedia.com. 17 Jul. 2014

Lewis, Samella, Ph.D. Two Sculptors Two Eras. Los Angeles: Landau/ Travelling Exhibitions, 1992.

Vertical files. Hancock County Historical Society.