This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

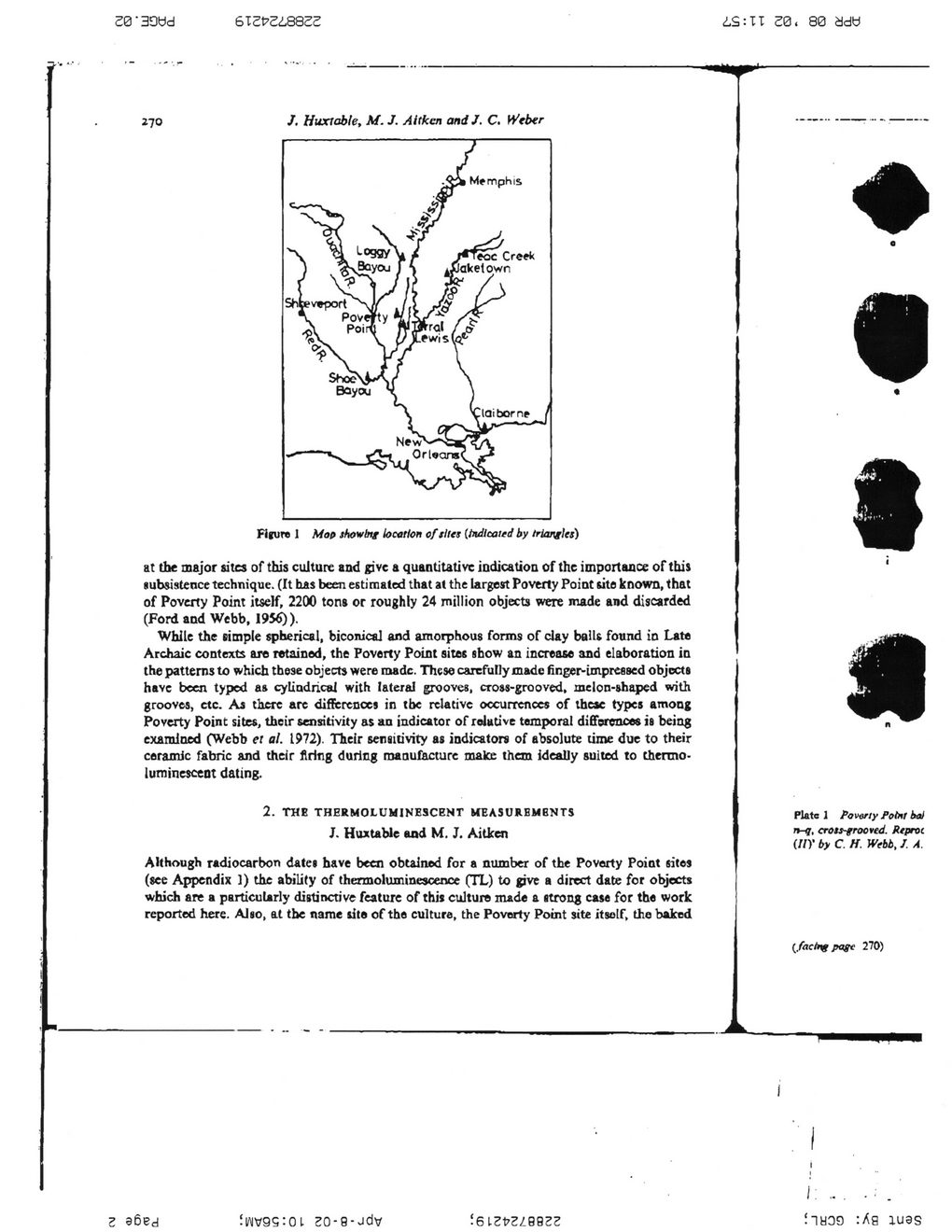

20'30Wd 6I2t72i8822 iS:TT 20. 80 ddti 270 7. Huxtable, M. J. Aitken and J. C. Weber at the major sites of this culture and give a quantitative indication of the importance of this subsistence technique. (It hits been estimated that at the largest Poverty Point site known, that of Poverty Point itself, 2200 tons or roughly 24 million objects were made and discarded (Ford and Webb, 1956)). While the simple spherical, biconic&l and amorphous forms of clay balls found in Late Archaic contexts are retained, the Poverty Point sites show an increase and elaboration in the patterns to which these objects were made. These carefully made finger-impressed objects have been typed as cylindrical with lateral grooves, cross-grooved, melon-shaped with grooves, etc. As there are differences in the relative occurrences of these types among Poverty Point sites, their sensitivity as an indicator of relative temporal differences is being examined (Webb et al. 1972). Their sensitivity as indicators of absolute time due to their ceramic fabric and their firing during manufacture make them ideally suited to thermoluminescent dating. 2. THE THERMOLUMINESCENT MEASUJRBMBNTS J. Huxtable and M. J. Aitken Although radiocarbon dates have been obtained for a number of the Poverty Point sites (see Appendix 1) the ability of thermoluminescence (TL) to give a direct date for objects which are a particularly distinctive feature of this culture made a strong case for the work reported here. Also, at the name site of the culture, the Poverty Point site itself, the baked ♦ Plato 1 /’overly Point tmJ n-q, crots-grooved. Reprot (//)' by C. H Webb, / A. (facing page 270) Z a6ed !lAIV9S:0l £0-9-Jdv 161ZPZ189ZZ ?1H39 :Ag 1U3S

Claiborne Historical Site Archaeometry-Pp-269-275-(02)