This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

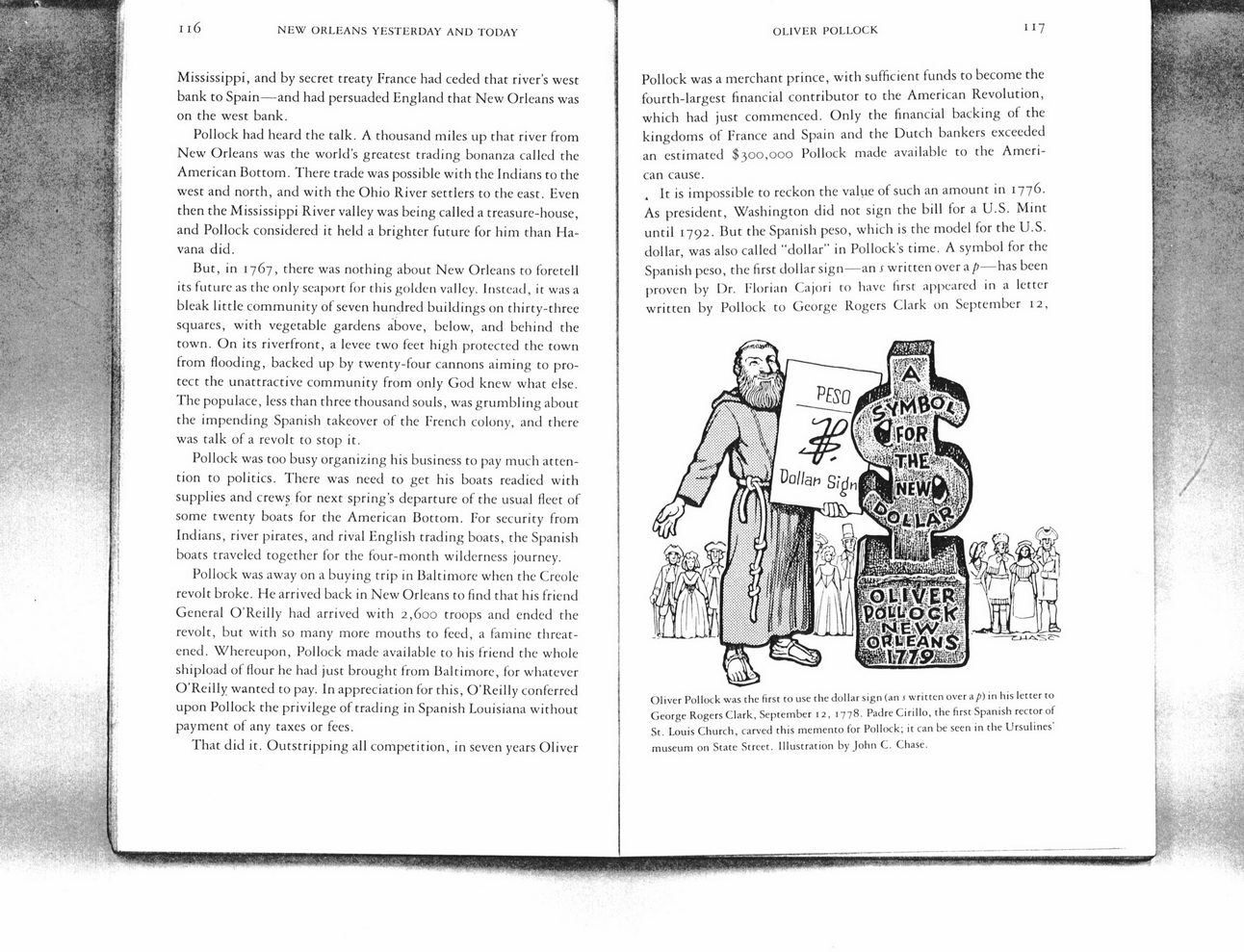

1 I I 6 NEW ORLEANS YESTERDAY AND TODAY Mississippi, and by secret treaty France had ceded that river's west bank to Spain?and had persuaded England that New Orleans was on the west bank. Pollock had heard the talk. A thousand miles up that river from New Orleans was the world's greatest trading bonanza called the American Bottom. There trade was possible with the Indians to the west and north, and with the Ohio River settlers to the east. Even then the Mississippi River valley was being called a treasure-house, and Pollock considered it held a brighter future for him than Havana did. But, in 1767, there was nothing about New Orleans to foretell its future as the only seaport for this golden valley. Instead, it was a bleak little community of seven hundred buildings on thirty-three squares, with vegetable gardens above, below, and behind the town. On its riverfront, a levee two feet high protected the town from flooding, backed up by twenty-four cannons aiming to protect the unattractive community from only God knew what else. The populace, less than three thousand souls, was grumbling about the impending Spanish takeover of the French colony, and there was talk of a revolt to stop it. Pollock was too busy organizing his business to pay much attention to politics. There was need to get his boats readied with supplies and crews for next spring's departure of the usual fleet of some twenty boats for the American Bottom. For security from Indians, river pirates, and rival English trading boats, the Spanish boats traveled together for the four-month wilderness journey. Pollock was away on a buying trip in Baltimore when the Creole revolt broke. He arrived back in New Orleans to find that his friend General O'Reilly had arrived with 2,600 troops and ended the revolt, but with so many more mouths to feed, a famine threatened. Whereupon, Pollock made available to his friend the whole shipload of flour he had just brought from Baltimore, for whatever O'Reilly wanted to pay. In appreciation for this, O'Reilly conferred upon Pollock the privilege of trading in Spanish Louisiana without payment of any taxes or fees. That did it. Outstripping all competition, in seven years Oliver OLIVER POLLOCK 117 Pollock was a merchant prince, with sufficient funds to become the fourth-largest financial contributor to the American Revolution, which had just commenced. Only the financial backing of the kingdoms of France and Spain and the Dutch bankers exceeded an estimated $300,000 Pollock made available to the American cause. . It is impossible to reckon the value of such an amount in 1776. As president, Washington did not sign the bill for a U.S. Mint until 1792. But the Spanish peso, which is the model for the U.S. dollar, was also called "dollar? in Pollock's time. A symbol for the Spanish peso, the first dollar sign?an s written over ap?has been proven by Dr. Florian Cajori to have first appeared in a letter written by Pollock to George Rogers Clark on September 12, Oliver Pollock was the first to use the dollar sign (an s written over ap) in his letter to George Rogers Clark, September 12, 1778. Padre Cirillo, the first Spanish rector of St. Louis Church, carved this memento for Pollock; it can be seen in the Ursulines' museum on State Street. Illustration by John C. Chase.

Pollock Family 006